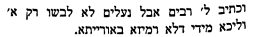

In Taama De'kra on parashat Ki Tavo, Rav Chaim Kanievsky writes:

That is, towards the end of Ki Tavo, Devarim 29, the pasuk states:

Though I don't think we need to try too hard to legitimize it. There are many strange things in Sefer Chassidim, which don't have a basis in the halacha or hashkafa of Chazal, nor were accepted as binding by the general Jewish community. Nor do we need to find an allusion to it in a pasuk.

There are various explanations floating around as to the meaning, and basis, of this position. (See Nit'ei Gavriel for a discussion.). For instance, some say this refers to shoes made from leather from a deceased (and therefore sick) animal. Some say it does refer to the shoes of a deceased person, but the problem is sweat from the deceased. Some say (Koret HaBrit) that the concern is that wearing such shoes will cause one to think about this during the day, and that those thoughts will cause one to dream about it at night, and we saw that this is a negative omen, and from this the sakana.

My problem with the last explanation is this. The idea that daytime thoughts cause the contents of nighttime dreams comes from the same approximate sugya in Berachot, about dreams, on 55b-56a:

(Complicating this is that dream interpretation was regarded as a science, And these is the well-developed idea of reality following whatever interpretation is offered, which seems to contrast with definitive explanations given for specific symbolism. And that certain types of dreams, over others, were understood to be prophetic, for instance, those which are repeated and occur towards the end of night, I think there are more than two positions to be had, and one member of Chazal might hold a nuanced position that cannot be neatly placed into Rationalist and non-Rationalist,)

Once we say that a particular dream is caused by daytime thoughts, I would argue that this strips it of its meaning, and its danger. Neither the Emperor of Rome nor King Shapur were put in danger by their dreams. If one wears the shoes of a deceased person and therefore dreams that dream mentioned by the gemara, there is no negative omen, and no danger in it. We should not conflate these two incompatible conceptions of dreams in order to create a prohibition, or an explanation for a prohibition.

That is, towards the end of Ki Tavo, Devarim 29, the pasuk states:

| ד וָאוֹלֵךְ אֶתְכֶם אַרְבָּעִים שָׁנָה, בַּמִּדְבָּר; לֹא-בָלוּ שַׂלְמֹתֵיכֶם מֵעֲלֵיכֶם, וְנַעַלְךָ לֹא-בָלְתָה מֵעַל רַגְלֶךָ. | 4 And I have led you forty years in the wilderness; your clothes are not waxen old upon you, and thy shoe is not waxen old upon thy foot. |

"לֹא-בָלוּ שַׂלְמֹתֵיכֶם מֵעֲלֵיכֶם, וְנַעַלְךָ לֹא-בָלְתָה מֵעַל רַגְלֶךָ -- Regarding clothing it is written in plural and by shoe it written in singular. And there is to say that here it hints to the Sefer Chassidim, siman 454, that one should not wear the shoes of a dead person (and see Berachot 57b). And therefore, the clothing, when one person dies, another could wear his clothing, so it is written in plural, but shoes, only one person can where them. And there is nothing which is not alluded to in the Torah."We can see the referred to item in Sefer Chassidim here:

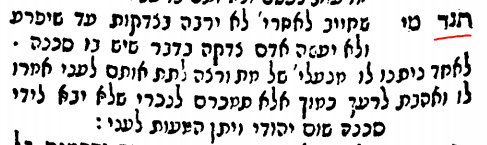

"One who owes others should not give a lot of charity, until he has repaid his debt. And a person should not give something dangerous as charity. If someone was given shoes of a deceased [מנעלים של מת] and wishes to give them to a pauper, they tell him "And you shall love your fellow as yourself!" Rather, sell them to a gentile so that no Jewish person comes to danger, and then give the money to the pauper."There are many explanations and rationalizations given to this statement in Sefer Chassidim. It can be connected to Berachot 57b, as Rav Kanievsky did above:

Our Rabbis taught: [If one dreams of] a corpse in the house, it is a sign of peace in the house; if that he was eating and drinking in the house, it is a good sign for the house; if that he took articles from the house, it is a bad sign for the house. R. Papa explained it to refer to a shoe or sandal. Anything that the dead person [is seen in the dream] to take away is a good sign except a shoe and a sandal; anything that it puts down is a good sign except dust and mustard.Perhaps we can say that the fact that Rav Papa, or the brayta, see a negative omen in a dreaming that dead man took shoes from a house indicates that this was regarded (legitimately, superstitiously, culturally) as a danger. If so, then perhaps this could in turn serve as a basis for idea presented by Rabbi Yehuda HaChassid.

Though I don't think we need to try too hard to legitimize it. There are many strange things in Sefer Chassidim, which don't have a basis in the halacha or hashkafa of Chazal, nor were accepted as binding by the general Jewish community. Nor do we need to find an allusion to it in a pasuk.

There are various explanations floating around as to the meaning, and basis, of this position. (See Nit'ei Gavriel for a discussion.). For instance, some say this refers to shoes made from leather from a deceased (and therefore sick) animal. Some say it does refer to the shoes of a deceased person, but the problem is sweat from the deceased. Some say (Koret HaBrit) that the concern is that wearing such shoes will cause one to think about this during the day, and that those thoughts will cause one to dream about it at night, and we saw that this is a negative omen, and from this the sakana.

My problem with the last explanation is this. The idea that daytime thoughts cause the contents of nighttime dreams comes from the same approximate sugya in Berachot, about dreams, on 55b-56a:

R. Samuel b. Nahmani said in the name of R. Jonathan: A man is shown in a dream only what is suggested by his own thoughts, as it says, As for thee, Oh King, thy thoughts came into thy mind upon thy bed.37 Or if you like, I can derive it from here: That thou mayest know the thoughts of the heart.38 Raba said: This is proved by the fact that a man is never shown in a dream a date palm of gold, or an elephant going through the eye of a needle.39

The Emperor [of Rome]1 said to R. Joshua b. R. Hananyah: You [Jews] profess to be very clever. Tell me what I shall see in my dream. He said to him: You will see the Persians2 making you do forced labour, and despoiling you and making you feed unclean animals with a golden crook. He thought about it all day, and in the night he saw it in his dream.3 King Shapor [I] once said to Samuel: You [Jews] profess to be very clever. Tell me what I shall see in my dream. He said to him: You will see the Romans coming and taking you captive and making you grind date-stones in a golden mill. He thought about it the whole day and in the night saw it in a dream.I would suggest that Chazal were not monolithic in their attitude towards dreams. Instead, there are at least two strains. A gross simplification would be to call one Rationalist and the other Mystical (or non-Rationalist), but it is a convenient gross simplification. The Rationalist position understood dreams as the synapses in the brain continuing to fire at night, such that we keep thinking about what we were thinking about during the day. The Mystical position took dreams as a form of prophecy, as messages from on high.

(Complicating this is that dream interpretation was regarded as a science, And these is the well-developed idea of reality following whatever interpretation is offered, which seems to contrast with definitive explanations given for specific symbolism. And that certain types of dreams, over others, were understood to be prophetic, for instance, those which are repeated and occur towards the end of night, I think there are more than two positions to be had, and one member of Chazal might hold a nuanced position that cannot be neatly placed into Rationalist and non-Rationalist,)

Once we say that a particular dream is caused by daytime thoughts, I would argue that this strips it of its meaning, and its danger. Neither the Emperor of Rome nor King Shapur were put in danger by their dreams. If one wears the shoes of a deceased person and therefore dreams that dream mentioned by the gemara, there is no negative omen, and no danger in it. We should not conflate these two incompatible conceptions of dreams in order to create a prohibition, or an explanation for a prohibition.