In a previous post on Vayikra, I noted how Rabbi Yosef Ibn Caspi didn't offer any commentary on the korbanot, because what Rashi and Ibn Ezra wrote already sufficed, and because

It turns out that this is one of the objections in the Ramban I linked to there:

וראוי שתרגיש ג״כ שקין והבל כל אחד מהם היה מכוין להתקרב אל השם במלאכתו, כי כל דרך איש ישר בעיניו.

"And it is appropriate to realize as well that Kayin and Hevel, each of them, intended to draw close to Hashem in his respective work, for all paths of man are right in his eyes."

So perhaps while Hevel's sacrifice was of similar form to later sacrifices, it took this form as a way of drawing close to Hashem within his chosen profession."

In another sefer, Ibn Caspi explains וישע as less than full desire, רצוי, found by korbanot in general.

וישע. אינו ריצוי גמור וירצה, כמו שיבא עוד בענין קרבנותינו

"וישע -- it is not complete ritzuy like vayeratzeh, like we find in the matter of our own korbanot"

So perhaps there is a sense here that the korban is not entirely appropriate even here. Neither of these is really a satisfying answer.

As I was listening to various shiurim on YUTorah.org this week, I came across this hour-long shiur from last year by Rabbi Netanel Wiederblank:

The shiur is titled: Rambam's controversial reason for the reason for korbanos. That reason is the one mentioned above, that it was modeled after the idolatrous practice of the surrounding nations, as a way of directing that drive.

At approximately the 5 minute mark, he mentions a series of question by the Ramban, and this question about Hevel's korban is one of them.

At the 35 minute mark, he addresses this Hevel question specifically. The Ritva (in sefer Zikaron, which you can read here) answers the question by saying that one needs to know the secret about what the Rambam writes about Kayin and Hevel. But unfortunately, the Ritva doesn't tell us what that secret it. The footnotes on the Ritva's sefer Zikaron send you to Moreh Nevuchim volume 2 perek 30. There, the idea is developed that neither Kayin nor Hevel were the ones to continue on humanity, but rather Shet was. And we see that Kayin was more physical and Hevel more non-physically oriented. But not in a good way. And their korbanot reflected their natures. So the takeaway is that even Hevel's korban was non-optimal.

But the summary I provided was third-hand. That is, my summary of Rabbi Wiederblank's understanding of the cryptic Rambam in Moreh Nevuchim, where it was already labeled a secret. And which is likely philosophical / mystical, and thus requires the necessary background intellectual background as well as an understanding of the rest of the chapter, as explained by the commentators of the Rambam.

The reference is to this in Moreh Nevuchim:

.וממה שצריך שתדעהו ג״כ ותתעורר

עליו׳ אופני ההנמה בקריאת בני אדם קין והבל והיות

קין הוא ההורג להבל בשדה, ושהם יחד אבדו אף על פי

שתאריך לרוצח,ושלא תתקיים המציאות אלא לשת כי שת לי אלהים זרע אהר הנה כבר התאמת זה

One should listen to the shiur directly. And one should see the Rambam inside.

I have seen this parasha and many of those [parshiyot] which follow it encircling the details of the zevachim and thekarbonot, which was written by Moshe Rabbenu in his sefer compelled and against his will, for there is no desire to Hashem in olot and zevachim [seeTehillim 51:18], but rather this was compelled by the practice of all the nations in that time which brought them to this.The Rambam holds similarly as to the purpose of the korbanot. In the comment section, a commenter recently asked:

How do [Ibn] Caspi and the Rambam account for Cain and Abel's sacrifices.This is a great question, because Kayin and Hevel were very early in the history of mankind, and therefore before the idolatrous practices of the nation. (Indeed, the generation of Enosh is where idolatry began.) If so, why would Kayin have brought korbanot from the plants and why would Hevel have brought korbanot from the flock? And Hashem liked Hevel's korban!

It turns out that this is one of the objections in the Ramban I linked to there:

והנה נח בצאתו מן התיבה עם שלשת בניו אין בעולם כשדי או מצרי הקריב קורבן וייטב בעיני ה' ואמר בו (בראשית ח כא): וירח ה' את ריח הניחוח. וממנו אמר אל לבו לא אוסיף עוד לקלל את האדמה בעבור האדם (שם). והבל הביא גם הוא מבכורות צאנו ומחלביהן, וישע ה' אל הבל ואל מנחתו (שם ד ד), ולא היה עדיין בעולם שמץ ע"ז כלל.We could check out what Ibn Caspi has to say in the incident of Kayin and Hevel. I am not sure how informative it is, exactly. He writes in one sefer:

וראוי שתרגיש ג״כ שקין והבל כל אחד מהם היה מכוין להתקרב אל השם במלאכתו, כי כל דרך איש ישר בעיניו.

"And it is appropriate to realize as well that Kayin and Hevel, each of them, intended to draw close to Hashem in his respective work, for all paths of man are right in his eyes."

So perhaps while Hevel's sacrifice was of similar form to later sacrifices, it took this form as a way of drawing close to Hashem within his chosen profession."

In another sefer, Ibn Caspi explains וישע as less than full desire, רצוי, found by korbanot in general.

וישע. אינו ריצוי גמור וירצה, כמו שיבא עוד בענין קרבנותינו

"וישע -- it is not complete ritzuy like vayeratzeh, like we find in the matter of our own korbanot"

So perhaps there is a sense here that the korban is not entirely appropriate even here. Neither of these is really a satisfying answer.

As I was listening to various shiurim on YUTorah.org this week, I came across this hour-long shiur from last year by Rabbi Netanel Wiederblank:

The shiur is titled: Rambam's controversial reason for the reason for korbanos. That reason is the one mentioned above, that it was modeled after the idolatrous practice of the surrounding nations, as a way of directing that drive.

At approximately the 5 minute mark, he mentions a series of question by the Ramban, and this question about Hevel's korban is one of them.

At the 35 minute mark, he addresses this Hevel question specifically. The Ritva (in sefer Zikaron, which you can read here) answers the question by saying that one needs to know the secret about what the Rambam writes about Kayin and Hevel. But unfortunately, the Ritva doesn't tell us what that secret it. The footnotes on the Ritva's sefer Zikaron send you to Moreh Nevuchim volume 2 perek 30. There, the idea is developed that neither Kayin nor Hevel were the ones to continue on humanity, but rather Shet was. And we see that Kayin was more physical and Hevel more non-physically oriented. But not in a good way. And their korbanot reflected their natures. So the takeaway is that even Hevel's korban was non-optimal.

But the summary I provided was third-hand. That is, my summary of Rabbi Wiederblank's understanding of the cryptic Rambam in Moreh Nevuchim, where it was already labeled a secret. And which is likely philosophical / mystical, and thus requires the necessary background intellectual background as well as an understanding of the rest of the chapter, as explained by the commentators of the Rambam.

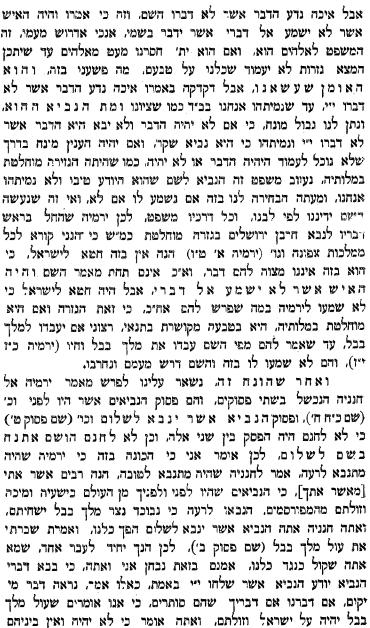

The reference is to this in Moreh Nevuchim:

.וממה שצריך שתדעהו ג״כ ותתעורר

עליו׳ אופני ההנמה בקריאת בני אדם קין והבל והיות

קין הוא ההורג להבל בשדה, ושהם יחד אבדו אף על פי

שתאריך לרוצח,ושלא תתקיים המציאות אלא לשת כי שת לי אלהים זרע אהר הנה כבר התאמת זה

One should listen to the shiur directly. And one should see the Rambam inside.