|

| Is sasgona hyacinth-colored? |

Summary: We saw in a

previous post that

sasgona is sky-blue. Did Rav Yosef, the expert Targumist, get this wrong? There are numerous other difficulties with the gemara, especially when compared with the parallel Yerushalmi. This post presents an admittedly

extremely speculative reconstruction of the original

sugya, in which a number of issues are resolved, and

tala ilan becomes

kala ilan.

Post: Some suggestions I make are more speculative than others. I want to make this clear, so that it does not undermine how people regard my methodology in general. In this post, I consider a gemara in Shabbos which discusses the identity of the

tachash. I have a number of "difficulties" with this gemara, and I will first lay them out briefly here, even though their meaning might not be obvious until we encounter the gemara:

1) Rabbi Nechemia says that the

tachash is

kemin tala ilan. It is strange that the

name of this

animal is so close to

kala ilan, an indigo dye, sky-blue, common in that time.

2) This, especially since as we saw in the

previous post that

sasgona was a dye which encompasses sky-blue, and that Josephus describes

tachash as sky-blue.

3) It is strange for Rav Yosef, an expert in Targumim, to render

sasgona in such a fanciful way, as the name of an animal which rejoices in its many colors, when there is a straightforward etymology (

sas gavna, worm color) and a Persian etymology, which make it a specific color,

such as sky-blue. (Yes, it could also mean scarlet, but regardless, it is a color.)

4) It is strange that while the beginning of Rav Yosef's statement uses Aramaic joiners (namely ד), the end part in which

sasgona is explained uses Hebrew joiners (namely ש). This suggests

setamaitic insertion/

5) It is strange that when Rav Yosef makes a statement and Rabbi Abba objects by citing a

brayta, the response and reinterpretation is not does by Rav Yosef by name, but is anonymous, and only

afterwards, does Rav Yosef seem to respond to this interpretation. Such anonymous Aramaic reinterpretation of sources, in the style of "like, but not exactly" is more

setamaitic in style. And that Rav Yosef even appears by name later also suggests this.

6) According to the straightforward reading of the

brayta,

both Rabbi Yehudah and Rabbi Nechemiah it is an animal rather than a dye. This is at odds with the Yerushalmi, in which one holds it is an animal and the other holds it is a dye.

7) In the parallel Yerushalmi, the objection that the

tachash would seem to be an animal, and a non-kosher one at that, comes from a

pasuk in Terumah which speaks of skins of

tachash. This would parallel Rabbi Yehuda's part of our

brayta, rather than Rabbi Nechemia's part? Why this disparity, and wouldn't it be nicer if the Bavli and Yerushalmi agreed?

8) The Yerushalmi resolves the question (of it seeming to be non-kosher) by answering that we hold like the one who holds it is a sky-blue dye; and indeed, cites a parallel dispute between Rabbi Yehuda and Rabbi Nechemia and chooses the one who says it is a dye. Wouldn't it be nicer if the Bavli and Yerushalmi agreed?

That is the short of it, but all of this difficulties and proofs make no sense until we see the relevant gemaras. The

gemara in Bavli Shabbos 28a:

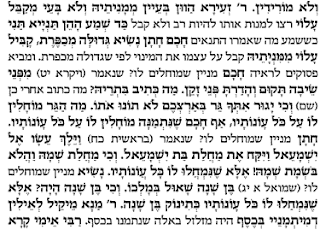

גופא בעי רבי אלעזר עור בהמה טמאה מהו שיטמא טומאת אהלין מאי קמיבעיא ליה אמר רב אדא בר אהבה תחש שהיה בימי משה קמיבעיא ליה טמא היה או טהור היה אמר רב יוסף מאי תיבעי ליה תנינא לא הוכשרו למלאכת שמים אלא עור בהמה טהורה בלבד. מתיב רבי אבא רבי יהודה אומר שני מכסאות היו אחד של עורות אילים מאדמים ואחד של עורות תחשים רבי נחמיה אומר מכסה אחד היה ודומה כמין תלא אילן והא תלא אילן טמא הוא ה"ק כמין תלא אילן הוא שיש בו גוונין הרבה ולא תלא אילן דאילו התם טמא והכא טהור א"ר יוסף א"ה היינו דמתרגמינן ססגונא ששש בגוונין הרבה

Or, in English:

[To revert to] the main text: 'R. Eleazar propounded: Can the skin

23 of an unclean animal be defiled with the defilement of tents?'

24 What is his problem?

25 — Said R. Adda b. Ahabah: His question relates to the tahash which was in the days of Moses,

26 — was it unclean or clean? R. Joseph observed, What question is this to him? We learnt it! For the sacred work none but the skin of a clean animal was declared fit.

R. Abba objected: R. Judah said: There were two coverings, one of dyed rams' skins, and one of tahash skins. R. Nehemiah said: There was one covering

27 and it was like a squirrel['s].

28 But the squirrel is unclean!-This is its meaning: like a squirrel['s], which has many colours, yet not [actually] the squirrel, for that is unclean, whilst here a clean [animal is meant]. Said R. Joseph: That being so, that is why we translate it sasgawna [meaning] that it rejoices in many colours.

29

As discussed in the previous post, 'squirrel' is how they are translating

tala ilan. But it is perhaps the genet, a spotted non-kosher animal of the civet family which hangs from trees.

One parallel Yerushalmi is here, in

Shabbos 16b going on to the next daf, Shabbos 17a:

דף טז, ב פרק ב הלכה ג גמרא

רבי אלעזר שאל מהו לעשות אוהל מעור בהמה טמאה. והכתיב ועורות תחשים.

דף יז, א פרק ב הלכה ג גמרא ר' יהודא ור' נחמיה ורבנן. ר' יהודא אומר טיינין לשם צובעו נקרא. ור' נחמיה אמר גלקטינין. ורבנן אמרין מין חיה טהורה. וגדילה במדבר.

"Rabbi Eleazar inquired: May one make a tent of the skin of a non-kosher species of animal? But it is written {in Teruma, in

Shemot 25:5}:

| ה וְעֹרֹת אֵילִם מְאָדָּמִים וְעֹרֹת תְּחָשִׁים, וַעֲצֵי שִׁטִּים. | 5 and rams' skins dyed red, and sealskins, and acacia-wood; |

{and the assumption is that this is a non-kosher animal -- at the very least, an

animal, as we might deduce from

Yechezkel 16:10.} {In fact, this is a matter of Tannaitic dispute:}

Rabbi Yehuda, Rabbi Nechemia, and the Sages. Rabbi Yehuda says it is taynin, and it was called after its color. {To cite

Sacred Monsters by Rabbi Natan Slifkin, Korban HaEidah says that these are ordinary goat skins dyed in that color, and the Aruch relates this particular color to jacintha, the blue hyancinth flower.}

And Rabbi Nechemia says it is galaktinin. {Once again, in

Sacred Monsters, Rabbi Slifkin cites Rabbi Binyamin Musafia that this is

gala + xeinon, meaning "foreign weasel.}

And the Sages say it was a species of kosher wild animal, which lived in the wilderness."

{Note: If it is hyacinth, then we can understand Rabbi Yehuda's statement, that it was called

taynin after its color, for the hyacinth color takes its name from the color of the hyacinth flower.}

This is fairly similar to our gemara, but our gemara differs in various respects. However,

in the end, I want to claim that the gemara is actually almost precisely the same. However, I'd like to first consider the difficulties I raised above in greater detail.

(1) What is this

תלא אילן? It seems to be a

hapax legomenon, a phrase that one occurs in one instance, namely in this gemara in Bavli Shabbos. We can

speculate as to its identity. After all,

tala means suspend and

ilan means tree, so it should be an animal which can hang from a tree. And the end of the gemara speaks of how it is joyous in its many colors, so we should look for a multicolored animal. Still, it is slightly (though not overwhelmingly) troubling that we have no way of really knowing its identity, while Rabbi Nechemiah makes the assumption that everyone knows what it is. Meanwhile, it would not be a

hapax legomenon if the word were slightly different,

קלא אילן, a known dye of a bluish color.

Kemin kala ilan would mean a bluish sort of dye, not precisely

kala ilan because that is the same hue as

techelet, mentioned earlier, but a different bluish dye. This interpretation would not work with the gemara as it now stands, however.

(2) We can promote this niggling doubt to a slightly greater level of concern when we note that Rav Yosef defines says in the very same gemara that we translate, in shul when we read the Targum,

techashim, as

ססגונא. Note that it is singular, rather than plural as we might expect if there were multiple

sasgonas as animals. And Shadal (in Ohev Ger, on Targum Onkelos) notes that there is no

de- beginning, namely

de-sasagona, and this makes it more of an adjective than a noun. Further, as we developed in the previous post,

sasgona is a

color, and likely is sky-blue. Thus, there are two references in this Bavli to dyes, both bluish. This interpretation of Rav Yosef would not work with the gemara as it now stands, however.

(3) Rav Yosef is

the expert in Targum. Assuming that this is the true meaning of

sasgona, blue, why would he get it so wrong?

sas +

gona = worm + color = whatever hue it is. Or, the Persian etymology. Regardless, it is an Aramaic word, and besides being an expert in etymology, he was an Amora of Bavel surrounded by Amoraim of Bavel. Surely

they would know that it was a specific color, namely a bluish hue.

(4) There are features of Rav Yosef's statement which make me question whether he said it all, or if some of it is a later interpolation by the

setama de-gemara. Namely, he says

א"ר יוסף א"ה היינו דמתרגמינן ססגונא ששש בגוונין הרבה.

The ד is Aramaic. The ש is Hebrew. The word

gavnin (colors) must still be Aramaic, because this is pulling apart the (fanciful) etymology of the Aramaic word. Still, it is this latter part of the entire statement, the part which is in Hebrew,

ששש בגוונין הרבה, which forces us into the particular interpretation of Rav Yosef's remarks, and creates the gemara as it now stands. Without this statement, he might still simply be saying that "this is why we translate it

sasgona". And that would still mean a bluish dye. This doesn't work out with the gemara as it now stands, of course, but it might be useful in some theoretical reconstructed gemara.

(5) When Amoraim have a conversation, I would expect each statement to be introduced by Amar Rabbi X, Amar Rabbi Y. Yet, considering our gemara, we have:

בעי רבי אלעזר עור בהמה טמאה מהו שיטמא טומאת אהלין

מאי קמיבעיא ליה

אמר רב אדא בר אהבה תחש שהיה בימי משה קמיבעיא ליה טמא היה או טהור היה

אמר רב יוסף מאי תיבעי ליה תנינא לא הוכשרו למלאכת שמים אלא עור בהמה טהורה בלבד

מתיב רבי אבא רבי יהודה אומר שני מכסאות היו אחד של עורות אילים מאדמים ואחד של עורות תחשים רבי נחמיה אומר מכסה אחד היה ודומה כמין תלא אילן

והא תלא אילן טמא הוא ה"ק כמין תלא אילן הוא שיש בו גוונין הרבה ולא תלא אילן דאילו התם טמא והכא טהור

א"ר יוסף א"ה היינו דמתרגמינן ססגונא ששש בגוונין הרבה

This entire statement, which I highlighted in

red, should have been spoken by Rav Yosef. After all, it

is his answer to Rabbi Abba's objection! Rather, it is an

anonymous Aramaic statement which understands

tala ilan to be an animal, and answers it by reinterpretation and harmonization, that of course the Tanna who said it was

kemin tala ilan, like a certain non-kosher animal, meant that it was

like but it differed in being kosher. This sort of anonymous Aramaic

slightly-forced harmonization is characteristic of a

setama de-gemara. Also, if Rav Yosef is saying it, should Amar Rav Yosef begin only after it? And why would he begin his statement with

א"ה, "if so", as if he is responding to someone else? I suppose we could say that Rabbi Abba posed the objection and then Rabbi Abba answered it, but this is slightly irregular.

(6) According to this

brayta, we have two positions, one from Rabbi Yehuda and one from Rabbi Nechemia:

רבי יהודה אומר שני מכסאות היו אחד של עורות אילים מאדמים ואחד של עורות תחשים

רבי נחמיה אומר מכסה אחד היה ודומה כמין תלא אילן

The objection is (seemingly) based on Rabbi Nechemiah in this

brayta, that he holds it is a

tala ilan. So he certainly maintains it is an

animal. Rabbi Yehuda also would seem, on a simple level, to treat it as an animal, since he says

אחד של עורות אילים מאדמים ואחד של עורות תחשים, putting

orot eilim opposite

orot techashim. This poses no problem since it could be this animal is kosher. (Like the Rabbanan of the Yerushalmi.) Or maybe it really is a dye, and the parallel is

מאדמים to

תחשים. But

if both are saying this is an animal, it is at odds with the

brayta in the Yerushlmi, where one held it was a dye and the other that it was an animal.

(7), (8) This brings us to the Yerushalmi, and contrasting and comparing the parallel sugyot.

They actually line up rather nicely. Bavli is in one font and Yerushalmi is in another, as above:

(a)

בעי רבי אלעזר עור בהמה טמאה מהו שיטמא טומאת אהלין

רבי אלעזר שאל מהו לעשות אוהל מעור בהמה טמאה.

Rabbi Eleazar (the Amora) poses a question about ritual impurity and tents. {

J: As an aside, I wonder if we could be gores

אוהל מעור as

ohel moed mei'or, with the seemingly duplicated word removed; this could bring it closer to the Bavli.}

(b)

מאי קמיבעיא ליה

אמר רב אדא בר אהבה תחש שהיה בימי משה קמיבעיא ליה טמא היה או טהור היה

והכתיב ועורות תחשים

In Bavli, we clarify that his question was actually regarding Moshe's

tachash. In Yerushalmi, this

tachash will be used as a proof, under the presumption that it is a non-kosher species. {I think.}

(c)

אמר רב יוסף מאי תיבעי ליה תנינא לא הוכשרו למלאכת שמים אלא עור בהמה טהורה בלבד

Rav Yosef makes the assumption that it must be a kosher species, such that that Tachash must be kosher. {

J: Maybe we could read this into the Yerushalmi's

והכתיב ועורות תחשים.)

(d)

מתיב רבי אבא רבי יהודה אומר שני מכסאות היו אחד של עורות אילים מאדמים ואחד של עורות תחשים רבי נחמיה אומר מכסה אחד היה ודומה כמין תלא אילן

ר' יהודא ור' נחמיה ורבנן. ר' יהודא אומר טיינין לשם צובעו נקרא. ור' נחמיה אמר גלקטינין. ורבנן אמרין מין חיה טהורה. וגדילה במדבר

A

brayta is brought. In the Bavli, it is Rabbi Nechemia who is difficult, since he refers to it as like a

tala ilan. {

J: is Yerushalmi's

taynin a cognate of Bavli's

tala ilan, in which case both are dyes?} In the Yerushalmi, it is Rabbi Nechemia who is difficult, since he explicitly refers to it as

gala xeinon, which is a foreign weasel, presumably an extant, non-kosher species.

Thus, in both Bavli and Yerushalmi, the problem comes from Rabbi Nechemia saying it is a non-kosher species.

(e)

The Yerushalmi leaves this alone, that there is indeed a problem based on Rabbi Nechemiah, but it is a matter of Tannaitic dispute. We can hold like Rabbi Yehuda or like the Sages, which would then make it goat skin dyed blue, or skins of a kosher wild animal. Both would present no problem.

In the Bavli, we like to harmonize and make it work out for everyone. Therefore,

מתיב רבי אבא רבי יהודה אומר שני מכסאות היו אחד של עורות אילים מאדמים ואחד של עורות תחשים רבי נחמיה אומר מכסה אחד היה ודומה כמין תלא אילן

והא תלא אילן טמא הוא ה"ק כמין תלא אילן הוא שיש בו גוונין הרבה ולא תלא אילן דאילו התם טמא והכא טהור

א"ר יוסף א"ה היינו דמתרגמינן ססגונא ששש בגוונין הרבה

And so it is really a kosher animal. The "problem" with this is that we know based on Yerushalmi that this is untrue. Rabbi Nechemia maintains it is a

gala xeinon, a foreign weasel, which is a non-kosher animal. And by speaking of a special animal, there are echoes of a specially created animal only available at that time which would be the Rabanin.

There is this disparity between Bavli and Yerushalmi. This is not catastrophic. These are different Amoraim behind the Bavli and Yerushalmi. Still, it would be nice if we could make them accord with one another.

--------------------------------

I have two reconstructions. In the

latter, I have to switch the positions of Rabbi Yehuda and Rabbi Nechemia. From what I recall, there are many times that the the positions are switched in different sources between this pair, so this is not so terrible. Still, I offer both reconstructions.

The

first:

בעי רבי אלעזר עור בהמה טמאה מהו שיטמא טומאת אהלין

מאי קמיבעיא ליה

אמר רב אדא בר אהבה תחש שהיה בימי משה קמיבעיא ליה טמא היה או טהור היה

אמר רב יוסף מאי תיבעי ליה תנינא לא הוכשרו למלאכת שמים אלא עור בהמה טהורה בלבד

מתיב רבי אבא רבי יהודה אומר :שני מכסאות היו אחד של עורות אילים מאדמים ואחד של עורות תחשים רבי נחמיה אומר מכסה אחד היה ודומה כמין תלא אילן

א"ר יוסף א"ה היינו דמתרגמינן ססגונא

'R. Eleazar propounded: Can the skin

23 of an unclean animal be defiled with the defilement of tents?'

24 What is his problem?

25 — Said R. Adda b. Ahabah: His question relates to the tahash which was in the days of Moses,

26 — was it unclean or clean? R. Joseph observed, What question is this to him? We learnt it! For the sacred work none but the skin of a clean animal was declared fit.

R. Abba objected: R. Judah said: There were two coverings, one of dyed rams' skins, and one of tahash skins. R. Nehemiah said: There was one covering

27 and it was like a squirrel['s].

28 But the squirrel is unclean!-This is its meaning: like a squirrel['s], which has many colours, yet not [actually] the squirrel, for that is unclean, whilst here a clean [animal is meant]. Said R. Joseph: That being so, that is why we translate it sasgawna

[meaning] that it rejoices in many colours.29

To explain, Rabbi Abba objects just as above, based on the

brayta. His objection is based on Rabbi Nechemiah, that this is like a

tala ilan, a non-kosher animal which climbs on trees. This is like the Yerushalmi, where Rabbi Nechemiah identifies it as a foreign weasel,

gala xeinon. There is no objection based on Rabbi Yehuda, since he gives no definition to

עורות תחשים. We can take this as skins of a kosher animal. Or

better, that

techashim is a color and parallels

מאדמים. The only problem is Rabbi Nechemiah.

Rabbi Yosef responds that

indeed, this is a matter of Tannaitic dispute. But we hold like Rabbi Yehuda. And so, Rav Yosef said: Since this is so, we render the Targum of it as

sasgana, which is a bluish dye. The Targum is supposed to accord with reality, which accords with

halacha. So we don't

pasken like Rabbi Nechemiah, and there is no issue.

The explanations crossed out above were from the

setama, which did not know the etymology and meaning of

sasgona, and assumed it was a kosher animal which took joy in its colors. Then, it transferred the idea of this animal to the

ke-kala ilan animal discussion above, such that Rav Yosef was

explaining Rabbi Nechemia, rather than

rejecting him.

I rather like this interpretation, and don't think we need to go any further. However, for the sake of completeness, and in order to explore the possibility, I will a second interpretation.

In the

second interpretation, there will be a cross between Rabbi Yehuda and Rabbi Nechemia, and the question in our gemara will be based on Rabbi Yehuda. Further,

tala ilan will become

kala ilan:

בעי רבי אלעזר עור בהמה טמאה מהו שיטמא טומאת אהלין

מאי קמיבעיא ליה

אמר רב אדא בר אהבה תחש שהיה בימי משה קמיבעיא ליה טמא היה או טהור היה

אמר רב יוסף מאי תיבעי ליה תנינא לא הוכשרו למלאכת שמים אלא עור בהמה טהורה בלבד

מתיב רבי אבא רבי יהודה אומר :שני מכסאות היו אחד של עורות אילים מאדמים ואחד של עורות תחשים רבי נחמיה אומר מכסה אחד היה ודומה כמין קלא אילן

א"ר יוסף א"ה היינו דמתרגמינן ססגונא

'R. Eleazar propounded: Can the skin23 of an unclean animal be defiled with the defilement of tents?'24 What is his problem?25 — Said R. Adda b. Ahabah: His question relates to the tahash which was in the days of Moses,26 — was it unclean or clean? R. Joseph observed, What question is this to him? We learnt it! For the sacred work none but the skin of a clean animal was declared fit.

R. Abba objected: R. Judah said: There were two coverings, one of dyed rams' skins, and one of tahash skins. R. Nehemiah said: There was one covering27 and it was like a squirrel['s] indigo.28 But the squirrel is unclean!-This is its meaning: like a squirrel['s], which has many colours, yet not [actually] the squirrel, for that is unclean, whilst here a clean [animal is meant]. Said R. Joseph: That being so, that is why we translate it sasgawna [meaning] that it rejoices in many colours.29

To explain, Rabbi Abba objects from Rabbi Yehuda, who seems to assume that there were two types of skins, that of the dyed ram's skins and the skins of the

tachash. This is in accord with the Rabbi Nechemia position of Yerushalmi. If it is an

animal skin, we might then assume based on other cues that the

tachash is a non-kosher animal. However, the position of Rabbi Nechemiah in Bavli is that it is a color, namely

kala ilan. (Or,

tala ilan, which might be a cognate of

taynin.)

Kala ilan is indigo, and

kemin kala ilan is a bluish hue. This accords well with Rabbi Yehuda in Yerushalmi, who identified it as

taynin, which is hyacinth, a bluish hue.

Rav Yosef then responds that indeed, we hold that it is a

kala ilan type of color, which is why we translate it in Targum as

sasgonin. And of course Rav Yosef, as an expert in Targum, is well placed to make such a statement.

While a Rabbi Nechemia and Rabbi Yehuda switch is not impossible (and if I recall correctly, not uncommon), and an emendation from

tala ilan to

kala ilan is not impossible, it is more difficult than the alternative. Still, it resolves even more of the "difficulties" I laid out above. I thought I'd spell out this possibility for completeness sake, but at the moment, I am leaning towards my first re-reading.