In parashat Vayechi, Yaakov crosses his hands when blessing Ephraim and Menasheh. Thus, the pasuk and Rashi:

It turns out that Saadia Gaon translates sikkel similarly, as sechel, and thus chochma:

Targum Onkelos then translates כִּי as arum, 'because'. I don't speak enough Arabic or Judeo-Arabic to see this, but according to Torah Shleima, Saadia Gaon translates כִּי here as 'despite':

בתרגום

רס״ג ז״ל, נתן שכל לידיו לעשות כן אף

כי מנשה היה הבכור:

Similarly Ibn Ezra, on both points:

which is to be taken as 'divert', rather than 'make foolish', And similarly in Yeshaya 44:25:

taken again as 'divert'. Consider the parallels in this pasuk, of mashiv achor.

Shadal (after listing the positions of Rashi et al and Rashbam et al) adopts as correct the position of his student R' Yitzchak Pardo, that he positioned his hands in a manner that those who saw would think that they had no knowledge, for after all, Menasheh was the Bechor. he notes that Abarbanel says similarly, though not precisely the same, using the term in a way contemporary philosophers used it, though that is not valid Biblical Hebrew.

| But Israel stretched out his right hand and placed [it] on Ephraim's head, although he was the younger, and his left hand [he placed] on Manasseh's head. He guided his hands deliberately, for Manasseh was the firstborn. | יד. וַיִּשְׁלַח יִשְׂרָאֵל אֶת יְמִינוֹ וַיָּשֶׁת עַל רֹאשׁ אֶפְרַיִם וְהוּא הַצָּעִיר וְאֶת שְׂמֹאלוֹ עַל רֹאשׁ מְנַשֶּׁה שִׂכֵּל אֶת יָדָיו כִּי מְנַשֶּׁה הַבְּכוֹר: | |

| He guided his hands deliberately: Heb. שִׂכֵּל. As the Targum renders: אַחְכִּמִינוּן, he put wisdom into them. Deliberately and with wisdom, he guided his hands for that purpose, and with knowledge, for he knew [full well] that Manasseh was the firstborn, but he nevertheless did not place his right hand upon him. | שכל את ידיו: כתרגומו אחכמינון, בהשכל וחכמה השכיל את ידיו (לכך, ומדעת), כי יודע היה כי מנשה הבכור, ואף על פי כן לא שת ימינו עליו: |

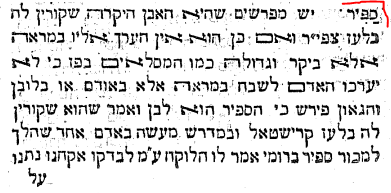

It turns out that Saadia Gaon translates sikkel similarly, as sechel, and thus chochma:

Targum Onkelos then translates כִּי as arum, 'because'. I don't speak enough Arabic or Judeo-Arabic to see this, but according to Torah Shleima, Saadia Gaon translates כִּי here as 'despite':

בתרגום

רס״ג ז״ל, נתן שכל לידיו לעשות כן אף

כי מנשה היה הבכור:

Similarly Ibn Ezra, on both points:

[מח, יד]This reflects one approach to sikel. The competing approach, or Rashbam and Ralbag, is to recognize the sin / samech switchoff, and to find the parallel in סכל, meaning to cross or make not straight. For instance, סַכֶּל-נָא in II Shmuel 15:31:

שכל את ידיו -כאלו ידיו השכילו, מה שהוא רוצה לעשות.

כי מנשה הבכור -אע"פ שמנשה הוא הבכור.

וכן: כי עם קשה עורף ורבים כן.

| לא וְדָוִד הִגִּיד לֵאמֹר, אֲחִיתֹפֶל בַּקֹּשְׁרִים עִם-אַבְשָׁלוֹם; וַיֹּאמֶר דָּוִד, סַכֶּל-נָא אֶת-עֲצַת אֲחִיתֹפֶל יְהוָה. | 31 And one told David, saying: 'Ahithophel is among the conspirators with Absalom.' And David said: 'O LORD, I pray Thee, turn the counsel of Ahithophel into foolishness.' |

which is to be taken as 'divert', rather than 'make foolish', And similarly in Yeshaya 44:25:

| כה מֵפֵר אֹתוֹת בַּדִּים, וְקֹסְמִים יְהוֹלֵל; מֵשִׁיב חֲכָמִים אָחוֹר, וְדַעְתָּם יְסַכֵּל. | 25 That frustrateth the tokens of the imposters, and maketh diviners mad; that turneth wise men backward, and maketh their knowledge foolish; |

taken again as 'divert'. Consider the parallels in this pasuk, of mashiv achor.

Shadal (after listing the positions of Rashi et al and Rashbam et al) adopts as correct the position of his student R' Yitzchak Pardo, that he positioned his hands in a manner that those who saw would think that they had no knowledge, for after all, Menasheh was the Bechor. he notes that Abarbanel says similarly, though not precisely the same, using the term in a way contemporary philosophers used it, though that is not valid Biblical Hebrew.