Summary: One is indeed a

pesik, and one should indeed be

darshened. Though I argue on the details. There is a vertical bar after

Machalat, and there is a

derasha that has Esav's sins forgiven with his marriage. Does this bar indicate the need for distancing oneself from one's past actions? There is a vertical bar after the

Shem Hashem in Avimelech's words to Yitzchak. Should this indicate that the wells ceased when Yitzchak left? Read on to find out!

Post: The very last pasuk in parashat Toledot reads (

28:9):

| 9. So Esau went to Ishmael, and he took Mahalath, the daughter of Ishmael, the son of Abraham, the sister of Nebaioth, in addition to his other wives as a wife. | | ט. וַיֵּלֶךְ עֵשָׂו אֶל יִשְׁמָעֵאל וַיִּקַּח אֶת מָחֲלַת בַּת יִשְׁמָעֵאל בֶּן אַבְרָהָם אֲחוֹת נְבָיוֹת עַל נָשָׁיו לוֹ לְאִשָּׁה: |

While in parashat Vayishlach, we have (

36:3):

| 2. Esau took his wives from the daughters of Canaan: Adah, daughter of Elon the Hittite; and Oholibamah, daughter of Anah, daughter of Zibeon the Hivvite; | | ב. עֵשָׂו לָקַח אֶת נָשָׁיו מִבְּנוֹת כְּנָעַן אֶת עָדָה בַּת אֵילוֹן הַחִתִּי וְאֶת אָהֳלִיבָמָה בַּת עֲנָה בַּת צִבְעוֹן הַחִוִּי: |

| 3. also Basemath, daughter of Ishmael, sister of Nebaioth. | | ג. וְאֶת בָּשְׂמַת בַּת יִשְׁמָעֵאל אֲחוֹת נְבָיוֹת: |

Both of these women are identified as the daughter of Yishmael and sister of Nevayot, and so it seems that they are the same person. And Rashi on Vayishlach reads:

| Basemath, daughter of Ishmael: Elsewhere [Scripture] calls her Mahalath (above 28:9). I found in the Aggadah of the midrash on the Book of Samuel (ch. 17): There are three people whose iniquities are forgiven (מוֹחֲלִים) : One who converts to Judaism, one who is promoted to a high position, and one who marries. The proof [of the last one] is derived from here (28:9). For this reason she was called Mahalath (מָחֲלַת), because his (Esau’s) sins were forgiven (נְמְחֲלוּ) . | | בשמת בת ישמעאל: ולהלן קורא לה (כח ט) מחלת. מצינו באגדת מדרש ספר שמואל (פרק יז) שלשה מוחלין להן עונותיהם גר שנתגייר, והעולה לגדולה, והנושא אשה, ולמד הטעם מכאן, לכך נקראת מחלת שנמחלו עונותיה: |

| sister of Nebaioth: Since he (Nebaioth) gave her hand in marriage after Ishmael died, she was referred to by his name. — [from Meg. 17a] | | אחות נביות: על שם שהוא השיאה לו משמת ישמעאל נקראת על שמו: |

|

Thus, they are the same person; and she is called מָחֲלַת here at the end of Toldos because his sins were forgiven.

Shadal makes two interesting points here:

את בשמת בת ישמעאל

: למעלה (כ"ח ט') נקראת מחלת, ונ"ל כי שני השמות ענינם אחד, כי מחלת לשון מתוק בל' ארמית, תרגום של מתוק חלי (כגון: שופטים י"ד י"ח) וכן בשם בארמית ענין מתיקות .ברש"י כ"י שבידי כתוב: עונותיה (לא עונותיו).ש

First, he suggests that Machalat and Basemat are related words, and gives an Aramaic etymology for Machalat meaning 'sweet'. Second, he mentions a

ktav yad of Rashi in his possession which has

עונותיה rather than

עונותיו.

In terms of the latter point, this is possibly not just a matter of slight girsological variance. The implication is that it is

her sins which were forgiven, not his.

However, I would note that that assumes that the ending of that word is Hebrew and should be read -

eha. But it could plausibly be read as Aramaic, as -

eih, in which case it still refers to

his sins.

We have the following in

Birkas Avraham:

בפסוק (בראשית כח ט, ) וילך עשו אל ישמעאל ויקח את מחלת בת ישמעאל בן אברהם וגו' . בתלמוד ירושלמי מס' ביכורים פ"ג ה"ג איתא, תניא תני, חכם , חתן , נשיא , גדולה , מכפרת. חתן, דכתיב וילך עשו וגו' , וכי מחלת שמה, והלא בשמת שמה ( פי' שבפרשת וישלח כתיב (בראשית ל"ו ג ) עשיו לקח וגו בשמת בת ישמעאל). אלא שנמחלו לה כל עונותיה, כך היא גירסת הר"ש סיריליאו ז"ל ובנוסחתנו כתוב שנמחלו לו כל עונותיו

וכן איתא בבראשית רבה בזה"ל , וילך עשו אל ישמעאל, רבי יהושע בן לוי אמר נתן דעתו להתגייר. מחלת, שמחל לו הקב"ה על כל עונותיו. בשמת, שנתבסמה דעתו עליו. אמר ר' אליעזר, אילו הוציא את הראשונות יפה היה, אלא על נשיו, כאב על כאב. ומכל מקום, מבואר במדרש שחתן מוחלין לו עוונותיו

והנה שתי דעות לפנינו במדרש, ולדעת רבי יהושע בן לוי שנמחלו לעשו עוונותיו, הוא הרהר תשובה במעשה זה, ורבי אליעזר טוען כנגדו שמעשיו מוכיחין שהוא לא נתכוון לפרוש מרשעותו, וממילא שלא נמחלו עוונותיו. ומעתה ברור שחתן הרוצה לזכות במחילת עוון, צריך להכין לבו לזה, ואז מוחלין לו עוונותיו. ובזה שונה הוא החתן משאר אנשים, שהאחרים צריכים להרבות בסוגי תשובה ותיקון החטאים .

ודע שעם דרשת חז"ל מ'מחלת' שנמחלין עוונות החתן והכלה, מובן טעם פסיק [קו] שאחרי תיבת מחלת כי אכן מה שהיה היה

ועתה פנים חדשות באו בלא רישום עוונות .

After citing the pasuk at the end of Toldos, he writes:

"In Talmud Yerushalmi, Masechet Bikurim, perek 3 halacha 3 there is {Josh: here, but rather messed up}: a Sage, a groom, a prince, greatness, atone... A groom, for it is written [in Toledot], וַיֵּלֶךְ עֵשָׂו אֶל יִשְׁמָעֵאל וַיִּקַּח אֶת מָחֲלַת. Now was her name מָחֲלַת? Was it not בָּשְׂמַת? (That is to say that in parashat Vaishlach is written "Esav took Basemat bat Yishmael.") Rather, all her sins were atoned for her, שנמחלו לה כל עונותיה. Such is the girsa of Rabbi Shlomo [ben Yosef] Sirillo [d. ca. 1558]. And in our nusach is written שנמחלו לו כל עונותיו, that all of his sins were forgiven."

Note the parallel to the two

girsaot in Rashi. One could also read the masculine into R' Sirillo's

girsa, with לה meaning לֵהּ, but still, it can be taken most readily to refer to her. Though it is strange. Why should we care about her and her sins?! Unlike Esav, she is a minor character not mentioned elsewhere, and we know of none of her sins. The girsa makes little sense to me. Besides, it says

chatan. And it is clear from the other examples in context.

You can see the gemara in full, with commentary by Yedid Nefesh,

here -- a great set of Yerushalmis to purchase, by the way:

At any rate, Birkas Avraham continues:

"And so is stated in Bereishit Rabba in this language:

"And Esav went to Yishmael... Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi said: He gave mind to convert. Machalat... that Hashem forgave him for all his sins. Basmat... that his mind was sweetened upon him.

Rabbi Eliezer said: If he had cast out the first ones, this would have been fine. But al nashav, 'upon his [other] wives', [understand this as] pain upon pain.

And yet, it is clear in the midrash that a groom, they forgive him his sins.

And behold, there are two opinions before us in the Midrash. And according to the opinion of Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi, that Esav was forgiven his sins, he thought to do teshuva with this act. And Rabbi Eliezer argues against him that his [=Esav's] actions prove that he did not intend to separate from his wickedness, and thus naturally, his sins were not forgiven. And thus, it is clear that a groom who wishes to take advantage of the forgiveness of iniquity needs to prepare his heart for this, and then his iniquities are atoned for. And with this, the groom differs from other men, that others require an abundance of types of teshuva and correction of the sins.

And know that which the derasha of Chazal from מחלת that the sins of the groom and the bride are atoned for, the pasek [vertical bar: | ] which is after the word Machalat is understood, for therefore, what was, was, and now new faces have come, with no impression of iniquities."

Birkas Avraham continues on at length with this

devar Torah, but I'll end my citation here.

Besides not being convinced that a

kallah is indeed included in this, I am not really convinced that the

derasha in Midrash Rabba is really of the same nature as that in Bikurim. The Midrash Rabba

reads:

וירא עשו כי רעות בנות כנען וילך עשו אל ישמעאל רבי יהושע בן לוי אמר:נתן דעתו להתגייר.

מחלת שמחל לו הקדוש ברוך הוא על כל עונותיו.

ש(בראשית לו) בשמת

שנתבסמה דעתו עליו.

אמר ר' אלעזר:אילו הוציא את הראשונות, יפה היה, אלא על נשיו, כאב על כאב.

דבר אחר: כוב על כוב, תוספת על בית מלא.

and the translation was more or less given above. I think that, while

one feed into the midrash was the difference between the two names and the connotation of

Mechila inherent in

Machalat, the first part of the pasuk (previously uncited), וירא עשו כי רעות בנות כנען, shows a possible change of heart on his part. And so, Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi

darshens the names in this way. And Rabbi Eleazar argues that this would not indicate a change of heart if he is still keeping those

benot kenaan who were bad in his parents' eyes, and so, the

derasha should not be made.

But not necessarily do

either of them say that simple

marriage is what causes the sins to be forgiven. Who says we need to bring in that idea from Yerushalmi Bikkurim? Rather, the change of heart indicated

teshuva, and then

both names should be interpreted in a positive manner, in which his act of choosing a

good girl this time demonstrates his change of heart.

If so, there is perhaps no

derasha of Chazal that explicitly indicates that a change of heart is necessary to obtain this

teshuva. Or course, it might well be

true, within Chazal's intention.

Here is where I get (even more)

nitpicky and argumentative, according to some. Birkas Avraham saw in this

derasha of Chazal, and in the detail that one must have a change of heart to take advantage of the exemption, justification / explanation for the

pesik after the word

Machalat. However, that is no

pesik. Rather, it is a

munach legarmeih!

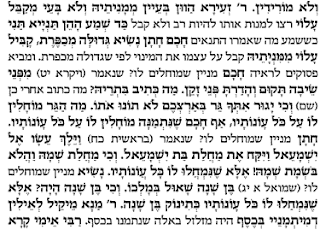

The pasuk looks like this -- I underlined the vertical bar in red:

Yes, it is a

munach legarmeih rather than a

psik, even though it does not appear before a

revii, but I will explain that point in a bit.

Now one can argue to salvage the

derasha on the vertical bar by pointing out the extreme likelihood that this was a deliberate choice on the part of the Masoretes to have a vertical bar functioning to turn the orthographic

munach, which is a conjunctive accent (

meshares) into a disjunctive accent (

melech). Thus, it is the bar causing a pause. I would admit to this, but would also point out that many other

melachim are modified

mesharsim. For instance, a

kadma and

pashta share a symbol. It is only position that distinguishes them. The same for

yesiv and

mahpach, and

telisha ketana and

gedola. In this instance, it was the addition of a

pasek after the word to indicate how to reinterpret the

munach, but the

munach is not really alone in being reinterpreted in this way. And in other systems of

trup orthography, they don't even use the vertical bar to mark the

legarmeih. (Rather, it is a script nun, the first letter of

neged, looking much like a

munach, appearing

over the word.)

One could also argue that a

geresh or

gershayim would be equally acceptable -- or in this instance, actually, a

telisha, and the choice of the

munach and

then the vertical bar to modify it makes it into a quasi-

pasek. Perhaps, but I am not convinced. Wickes argues that this regular though optional divergence occurs in specific scenarios, and is simply to provide musical variation. I don't think we interpret every

pashta and

tipcha, so neither should we interpret every

munach legarmeih. It is not the same as a

pesik which occurs over and above the ordinary divergence provided by

trup, and often appears for semantic rather than

semantic syntactic purposes. And I think Birkas Avraham would agree.

Even so, in this instance, something strange

is indeed going on. If this is a

munach legarmeih, then how come it is not in

revii's clause. The separating

trup symbol which follows is a

geresh, not a

revii!

William Wickes writes that in almost all instances, a

revii will follow a

legarmeih. But, there are a total of 11 exceptions in the entirety of Tanach:

Note that out

Machalat pasuk is the first one listed. So forget about

pasek! Our

legarmeih is unique and, even according to Wickes, called out

darsheni!

What could be the

derasha here? I still don't think that it is what Birkas Avraham wrote, that it is the separation from one's previous actions. Nor is it that it is the last pasuk of the

sidra (assuming that this was a

possible motivating factor, and they did not use the

parshiyot of Eretz Yisrael). Rather, it is that

Machalat differs from

Basemat elsewhere. And that, then, deserves special notice or special emphasis. Then, of course, kick in the

derasha about Esav's sins being forgiven.

There is another place that Birkas Avraham

darshens a

pesik. And in this instance, it most certainly

is a

pesik. The pasuk is in Bereishit 26:28, and describes Avimelech coming to make peace with Yitzchak. This is what they say:

Yes, the vertical bar is after a

munach, and there is a

revii in close proximity. But intervening is the

segolta, which is basically a

zakef. The clause belongs to the

segolta, not to the

revii. And the first dividing accent before it is the

zarka on ראינו. There are two

munachs in between, which is acceptable. Indeed can have long runs of

munach. But still, there is the

shem Hashem there, and it should be divided from the following word. This is the type of

psik that

Wickes refers to as

paseq emphaticum.

Birkas Avraham

writes:

When Yitzchak left Gerar, the wells stopped [פסקו], and therefore they said ראו ראינו [we have seen], and it is hinted in the pesik [פסק]

In the verse {and he cites it}, there is a pesik [ a vertical bar: | ] between the words יקוק and לעמך. Certainly they did not intend to say that this has ceased, that Hashem was with him, for behold they said that this they have seen, that Hashem was with him. Rather, it appears that it hints to that which is in Targum {Pseudo-}Yonatan Ben Uziel here, that they said to him that they saw with their eyes that Hashem was in his aid, for in his merit was to them all the good, and that when he left their land the wells dried up and the trees did not produce fruit. And now is understood as well the trup symbol of pesik, which hints to the ceasing [פסיקת] of the waters of the wells, and the fruits, with him.

An admittedly clever and creative explanation. Though I don't think it is necessary. The

pesik does not have to refer to the ceasing of Hashem being with Yitzchak if it were not

darshened in this other manner. Rather, it need not be

darshened at all. It simply stands to give the Shem Hashem its proper reverence, just as it does in many other instances.