Post: I have a particular interest in how the classic meforshim regarded nikkud and trup. Was it received tradition MiSinai, in which case one cannot argue on it, or was it simply a very ancient (and therefore important) commentary / interpretation? Shadal discusses this in his Vikuach, in terms of many of the classic commentators, where he claims that they all reserved the right to argue on both nikkud and trup. But I saw some interesting comments by Ibn Caspi, in which he maintains that trup and nikkud are from the Anshei Knesset HaGedolah, yet based on received tradition from Moshe Rabbenu. And therefore the trup and nikkud are definitive when it comes to peshat. I discussed his position this last week on Vayeishev in terms of tzadeka mimeni, where he appears to say that the lack of disjunctive trup dividing tzadeka mimeni means that the Divine intent in that pasuk is one statement, "she is more righteous than I."

One interesting comment in this realm is as regards an apparent heh heshe'eilah, which he claims is not one at all. In Miketz, in Bereishit 43:6:

| ו וַיֹּאמֶר, יִשְׂרָאֵל, לָמָה הֲרֵעֹתֶם, לִי--לְהַגִּיד לָאִישׁ, הַעוֹד לָכֶם אָח. | 6 And Israel said: 'Wherefore dealt ye so ill with me, as to tell the man whether ye had yet a brother?' |

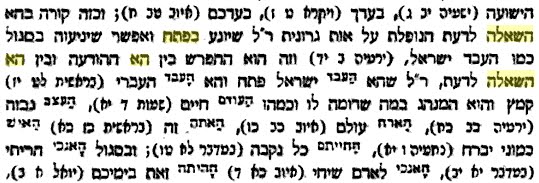

ה(ו) העוד לכם אח, אין הה"א בכאן לתמה ושאלה, וכן

ה"א העולה היא למעלה (קהלת ג׳ כ"א), ופרשו לנו זה אנכה״נ כי

•שמו תחתיו קמץ:

haOd lachem ach -- the heh here is not for astonishment and query, and so too the heh of haOlah hi leMaalah (Kohelet 3:21). And the Men of the Great Assembly explained it to us, for they placed under it a kamatz.However, a simple examination of the word haOd reveals that there is a patach there! Maybe he has different names for these nekudot? He does not,

because he refers us to the pasuk in Kohelet, and there, indeed, there is a kamatz in haOlah:

| כא מִי יוֹדֵעַ, רוּחַ בְּנֵי הָאָדָם--הָעֹלָה הִיא, לְמָעְלָה; וְרוּחַ, הַבְּהֵמָה--הַיֹּרֶדֶת הִיא, לְמַטָּה לָאָרֶץ. | 21 Who knoweth the spirit of man whether it goeth upward, and the spirit of the beast whether it goeth downward to the earth? |

Thus, he actually has a different tradition, or variant text, in which there is a kamatz under the heh. This is at odds with the Leningrad Codex, not just our own Chumashim. And I did not see Minchas Shai mention any variant. Perhaps someone knows where this variant occurs?

He makes a valid grammatical point, were the text indeed as he specified. And he did not invent this idea. We can turn to Ibn Janach's Sefer HaRikmah, since we know that Ibn Caspi wrote a commentary on that sefer. And Ibn Janach writes:

Thus, there is this difference between heh hayediah and heh hashe'eilah. Not just that in the normal form the heh of queries gets a chataf patach while the heh of definite articles gets a full patach, followed by a dagesh, but when each are followed by a guttural, they also take different forms.

And indeed, this makes sense. The regular patach dagesh cannot place its dagesh in the ayin, and so it undergoes compensatory lengthening and becomes a kametz. And the chataf patach for other reasons becomes a patach. So they are different in form, such that we can distinguish one for another.

To digress to that pasuk in Kohelet, as translated above by JPS, it is rather heretical! It appears to be questioning the idea of Olam Haba! Again, that pasuk:

| כא מִי יוֹדֵעַ, רוּחַ בְּנֵי הָאָדָם--הָעֹלָה הִיא, לְמָעְלָה; וְרוּחַ, הַבְּהֵמָה--הַיֹּרֶדֶת הִיא, לְמַטָּה לָאָרֶץ. | 21 Who knoweth the spirit of man whether it goeth upward, and the spirit of the beast whether it goeth downward to the earth? |

Indeed, this brings to mind that Chazal argued whether to include sefer Koheles in the Biblical canon, or whether it should be nignaz. But the nikkud of the first and second part of the pasuk transform the pasuk, such that it presents an entirely different idea. The kametz of haolah is matched by the patach dagesh of hayyoredet. Thus, both are the heh indicating the definite article.

And so many meforshim interpret it in this way, precisely in accordance with the nikkud. I am not certain what to make of Rashbam:

Since he is saying that no one knows that X goes up and Y goes down. I don't know how he precisely interprets the grammatical point, but the semantic point seems awfully close to what we saw above.

Midrash Rabba more clearly assumes that this is referring to tzaddikim who certainly are ascending up. Thus,

On the other hand, Rabbi Yeshaya de Trani clearly does explicitly interpret in accordance with the nikkud. Thus,

כא. מי יודע רוח בני האדם העולה היא למעלה: אין לומר שה"א זו היא ה"א התימה ולפרש אם עולה היא למעלה, ורוח הבהמה אם יורדת היא למטה, שאם כן היה לה להינקד בחטף פתח, ככל ה"א התימה, ועוד כי הוא בעצמו אמר בסוף זה הספר (יב-ז) "הרוח תשוב אל האלוהים אשר נתנה", אלמא הוא דבר ידוע, אלא ה"א זו היא ה"א הידיעה, וכך הוא פירושו: "רוח בני האדם העולה היא למעלה" בודאי, "ורוח הבהמה היורדת היא למטה" בודאי, מי זה בן אדם יודע אותו בהכרת מראה, שיוכל אדם לומר: טוב אני מן הבהמה מפני שרוחי עולה לשמים.

He notes the kametz. And furthermore, there appears to be an internal contradiction with what is stated later in Kohelet, that the spirit returns to God. (Although I would note that apparent or real internal contradictions are one thing that caused Chazal to want to exclude it from the Biblical canon.) Rather, certainly the spirit of man ascends while certainly the spirit of animal descends, but which person is able to know this via direct observation, so as to be able to say that he is better than the animals because of this.

R' Baruch Epstein in Gishmei Bracha solves the problem in a different way, transferring it from uncertainty and possible heresy into certainty, in a different way. Though I don't know if he is specifically relying on the nikkud. I think one can say what he says even if there were chataf patachs present.

Ibn Janach, as well as Menachem Saruk, explicitly make this grammatical point:

And, of course, Rashi appears to read it this way:

Who knows: Like (Joel 2: 14): “Whoever knows shall repent.” Who is it who understands and puts his heart to [the fact] that the spirit of the children of men ascends above and stands in judgment, and the spirit of the beast descends below to the earth, and does not have to give an accounting. Therefore, one must not behave like a beast, which does not care about its deeds. |

This is in the case of Kohelet, where I wonder if the nikkud represents an interpretive attempt to clean up the theology. (This, if nikkud is commentary rather than purely tradition.) In terms of our own parsha, of Miketz, we don't have this nikkud, though Ibn Caspi does, and thus feels compelled to follow it.

In Miketz, it makes for only a slightly awkward interpretation, if it all. Instead of :

| ו וַיֹּאמֶר, יִשְׂרָאֵל, לָמָה הֲרֵעֹתֶם, לִי--לְהַגִּיד לָאִישׁ, הַעוֹד לָכֶם אָח. | 6 And Israel said: 'Wherefore dealt ye so ill with me, as to tell the man whether ye had yet a brother?' |

Ibn Caspi discusses nikkud and its authority a bit earlier in Miketz as well. And there he makes clear that nikkud is from Anshei Knesset Hagedolah, who got it from Moshe. I plan on exploring that other statement in a subsequent post.

No comments:

Post a Comment