In

Taama deKra on Vayera, Rav Chaim Kanievsky points out an interesting discrepancy between Rashi on Vayera and Rashi on Balak:

That is, the pasuk and Rashi in Vayera (

Bereishit 22:3) read:

| And Abraham arose early in the morning, and he saddled his donkey, and he took his two young men with him and Isaac his son; and he split wood for a burnt offering, and he arose and went to the place of which God had told him. | | ג. וַיַּשְׁכֵּם אַבְרָהָם בַּבֹּקֶר וַיַּחֲבשׁ אֶת חֲמֹרוֹ וַיִּקַּח אֶת שְׁנֵי נְעָרָיו אִתּוֹ וְאֵת יִצְחָק בְּנוֹ וַיְבַקַּע עֲצֵי עֹלָה וַיָּקָם וַיֵּלֶךְ אֶל הַמָּקוֹם אֲשֶׁר אָמַר לוֹ הָאֱלֹהִים: |

| his two young men: Ishmael and Eliezer, for a person of esteem is not permitted to go out on the road without two men, so that if one must ease himself and move to a distance, the second one will remain with him. — [from Pirkei d’Rabbi Eliezer, ch. 31; Gen. Rabbah ad loc., Tan. Balak 8] | | את שני נעריו: ישמעאל ואליעזר, שאין אדם חשוב רשאי לצאת לדרך בלא שני אנשים, שאם יצטרך האחד לנקביו ויתרחק יהיה השני עמו: |

while the pasuk and Rashi in Balak (Bemidbar 22:22)

read:

| God's wrath flared because he was going, and an angel of the Lord stationed himself on the road to thwart him, and he was riding on his she-donkey, and his two servants were with him. | | כב. וַיִּחַר אַף אֱלֹהִים כִּי הוֹלֵךְ הוּא וַיִּתְיַצֵּב מַלְאַךְ יְהֹוָה בַּדֶּרֶךְ לְשָׂטָן לוֹ וְהוּא רֹכֵב עַל אֲתֹנוֹ וּשְׁנֵי נְעָרָיו עִמּוֹ: |

| and his two servants were with him: From here we learn that a distinguished person who embarks on a journey should take two people with him to attend him, and then they can attend each other [so that when one is occupied, the other takes his place]. — [Mid. Tanchuma Balak 8, Num. Rabbah 20:13] | | ושני נעריו עמו: מכאן לאדם חשוב היוצא לדרך יוליך עמו שני אנשים לשמשו וחוזרים ומשמשים זה את זה: |

In both cases, Rashi states that this is

derech eretz to have two men to attend him. However, in Vayera, Rashi states explicitly that it so that if one attendant needs to defecate, which requires moving to a distance, the other can remain with him. Meanwhile, in Balak, Rashi appears to say that besides attending him, they are attending each other. [The bracketed text in English in the second Rashi is an attempted harmonization, rather than something explicit in Rashi.] This seems to indeed be a discrepancy.

Rav Chaim Kanievsky offers a rather clever resolution. He points to

Sanhedrin 104b [the citation in the text which has

105b is in error] which states:

Our Rabbis taught: It once happened that two men [Jews] were taken captive on Mount Carmel, and their captor was walking behind them. One of them said to the other, 'The camel walking in front of us is blind in one eye, and is laden with two barrels, one of wine, and the other of oil, and of the two men leading it, one is a Jew, and the other a heathen.' Their captor said to them, 'Ye stiff-necked people, whence do ye know this?' They replied, 'Because the camel is eating of the herbs before it only on the side where it can see, but not on the other, where it cannot see.1 It is laden with two barrels, one of wine and the other of oil: because wine drips and is absorbed [into the earth], whilst oil drips and rests2 [on the surface].3 And of the two men leading it, one is a Jew, and the other a heathen: because a heathen obeys the call of Nature in the roadway, whilst a Jew turns aside.' He hastened after them, and found that it was as they had said.4 So he went and kissed them on the head,5 brought them into his house, and prepared a great feast for them. He danced [with joy] before them and exclaimed 'Blessed be He who made choice of Abraham's seed and imparted to them of His wisdom, and wherever they go they become princes to their masters!' Then he liberated them, and they went home in peace.

The relevant portion of this tale is that the captive Jews reasoned that ahead of them on the road was one Jew and one gentile, 'because a heathen obeys the call of Nature in the roadway, whilst a Jew turns aside'. If so, for Avraham and his servants, the explanation of turning aside works. Meanwhile, from Bilaam and his servants, the explanation of turning aside does not work.

This is a rather neat resolution. I suspect that, besides a

bekius in Shas, the connection was aided by the proximity of Sanhedrin 104b, with this tale, to Sanhedrin 105a, which discusses midrashim about Bilaam, in reference to the events of parashat Balak.

Still, I don't think that this resolution is correct. Here are a few objections:

_____

1) Avraham went with Eliezer and Yishmael, and Bilaam went with two servants. The ones who would distance themselves in this scenario would be Eliezer, Yishmael and [not] the two servants. If so, the contrast is not between Avraham and Bilaam, but of their

attendants. Still, this particular objection can be readily dismissed. Eliezer (as an

eved kenaani) and Yishmael (as son of Avraham) would be expected to conduct themselves appropriately, distancing themselves when relieving themselves.

2) More to the point, when these Rashis speak of

derech eretz for an

adam chashuv, the idea is that this is conduct with

dignity. Both Avraham and Bilaam momentarily abandoned that dignity, Avraham for

zerizut for the

mitzvah and Bilaam for hatred (see the Rashis in proximity). Yet here, in taking two attendants, they are conducting themselves with dignity.

When the gemara in Sanhedrin speaks, in the tale, of the difference between Jews and heathens, in that Jews will turn aside while the heathens will defecate in the middle of the road, the point of distinction is that the Jews are conducting themselves with

dignity. Bilaam, conducting himself as an

adam chashuv, would not defecate in the middle of the road. What of the attendants? Do you really think it dignified for Bilaam to be attended upon by a servant while the servant defecates next to him on the road?

3) The wording of Rashi (drawn from Midrash Tanchuma) is

מכאן לאדם חשוב היוצא לדרך יוליך עמו שני אנשים לשמשו וחוזרים ומשמשים זה את זה. That is, we, who are Jewish people, are supposed to derive a lesson of proper conduct for a Jewish

adam chashuv from this. Would the midrash really, then, substitute a weaker reason (of them attending one another) which only is relevant to non-Jews?

____

Some commentators note this discrepancy in Rashi and attempt to harmonize. For instance, see

Siftei Chachamim on the Rashi in Balak, where the "attending on one another" is that one does the attending that the other would do, when one of them excuses himself to use the bathroom.

Etz Yosef on the Midrash Tanchuma in Balak says likewise. This is a plausible harmonization, though one needs to force it into the words a bit. The simpler meaning is that the attendants attend one another. The man is so

chashuv that even his attendants have attendants!

I would rather not focus (for now at least) on the meaning of these two statements. Maybe one

should harmonize, and Tanchuma means the same as what Rashi said in Vayera, and maybe one should

not harmonize.

However, I would guess that the reason for the difference in Rashi stems from a difference in wording from Rashi's sources. That is, Rashi does not typically make things up, based on

sevara, but rather channels

midrashim. We saw Rashi's sources cited above. Let us repeat them. In Vayera:

| And Abraham arose early in the morning, and he saddled his donkey, and he took his two young men with him and Isaac his son; and he split wood for a burnt offering, and he arose and went to the place of which God had told him. | | ג. וַיַּשְׁכֵּם אַבְרָהָם בַּבֹּקֶר וַיַּחֲבשׁ אֶת חֲמֹרוֹ וַיִּקַּח אֶת שְׁנֵי נְעָרָיו אִתּוֹ וְאֵת יִצְחָק בְּנוֹ וַיְבַקַּע עֲצֵי עֹלָה וַיָּקָם וַיֵּלֶךְ אֶל הַמָּקוֹם אֲשֶׁר אָמַר לוֹ הָאֱלֹהִים: |

| his two young men: Ishmael and Eliezer, for a person of esteem is not permitted to go out on the road without two men, so that if one must ease himself and move to a distance, the second one will remain with him. — [from Pirkei d’Rabbi Eliezer, ch. 31; Gen. Rabbah ad loc., Tan. Balak 8] | | את שני נעריו: ישמעאל ואליעזר, שאין אדם חשוב רשאי לצאת לדרך בלא שני אנשים, שאם יצטרך האחד לנקביו ויתרחק יהיה השני עמו:

|

I've looked at

Pirkei deRabbi Eliezer, perek 31, and saw no reference to

adam chashuv. I think they are simply sourcing the identification of these two young men as Yishmael and Eliezer. This identification indeed appears in Pirkei deRabbi Eliezer. See line 23-24:

Bereishit Rabba 55:7 has this source for Rashi:

ויקח את שני נעריו אתו.

אמר רבי אבהו:שני בני אדם נהגו בדרך ארץ: אברהם ושאול.

אברהם, שנאמר: ויקח את שני נעריו.

שאול, (ש"א כ"ח) וילך הוא ושני אנשים עמו.

"And he took his two young men with him. Rabbi Abahu said: two people conducted themselves with derech eretz, namely Avraham and Shaul. Avraham, as it is said 'And he took his two young men with him'. Shaul, (I Shmuel 28) 'And he went, and two men with him'."

Note that Rabbi Abahu here does not reckon Bilaam as one who conducted himself with

derech eretz. Bilaam is not on the radar.

Neither of these two sources speak specifically about the

reason for two attendants. Perhaps Rashi supplemented this himself. Perhaps he looked to the distance, and was indeed interpreting Tanchuma on Balak. I still would not leap to say that he drew this from Balak. Perhaps there is still some other midrashic source which states this explicitly.

The pasuk and Rashi in Balak were:

| God's wrath flared because he was going, and an angel of the Lord stationed himself on the road to thwart him, and he was riding on his she-donkey, and his two servants were with him. | | כב. וַיִּחַר אַף אֱלֹהִים כִּי הוֹלֵךְ הוּא וַיִּתְיַצֵּב מַלְאַךְ יְהֹוָה בַּדֶּרֶךְ לְשָׂטָן לוֹ וְהוּא רֹכֵב עַל אֲתֹנוֹ וּשְׁנֵי נְעָרָיו עִמּוֹ: |

| and his two servants were with him: From here we learn that a distinguished person who embarks on a journey should take two people with him to attend him, and then they can attend each other [so that when one is occupied, the other takes his place]. — [Mid. Tanchuma Balak 8, Num. Rabbah 20:13] | | ושני נעריו עמו: מכאן לאדם חשוב היוצא לדרך יוליך עמו שני אנשים לשמשו וחוזרים ומשמשים זה את זה:

|

We can safely ignore Bamidbar Rabba, which is likely post-Rashi and does not serve as Rashi's source (and which says the same as Tanchuma anyway). Rashi got this from

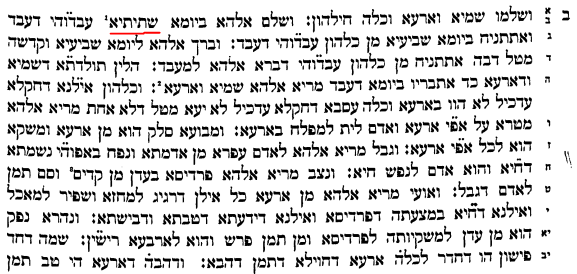

Tanchuma Balak, which states:

ושני נעריו עמו זה דרך ארץ, אדם חשוב היוצא לדרך, צריך שנים לשמשו, וחוזרין ומשמשין זה לזה.

Note that Tanchuma on parashat Vayera takes no note of Avraham taking along two attendants.

The picture I am trying to draw here is of two midrashim which operate in parallel, which do not know of each other. Rabbi Abahu in Bereishit Rabba only knows of Avraham and Shaul and does not know of Bilaam. Midrash Tanchuma only knows of Bilaam and does not know of Bilaam. If so, the reasoning within these two midrashic traditions also do not need to match. (To return to the topic of whether one should harmonize, this might help strip our impetus to harmonize the Rashis.)

And don't complain to Rashi about discrepancies. Rashi in Balak did not say the explanation of an attendant distancing himself to defecate because he was citing Midrash Tanchuma verbatim. He would not have changed the midrash without cause. Perhaps one could complain to Rashi about his explanation in Vayera, but then, we don't necessarily have Rashi's source.