Rivkah's family says that they will put the question whether she will go to Rivkah. Bereshit 24:

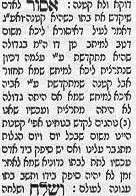

On pasuk 57, Rashi writes:

or in English:נז) ונשאלה את פיה -

מכאן שאין משיאין את האשה אלא מדעתה:

The thing is, when we actual look it up in Midrash Rabba, we see that Rashi seems to be a bit off in his citation. Bereshit Rabba actually says:And ask her From here we learn that we may not marry off a woman except with her consent. — [Gen. Rabbah 60: 12]

ויאמרו נקרא לנערה, מכאן שאין משיאין את היתומה אלא על פיהThe change is from yetoma to isha.

In context in Midrash Rabba, the idea is that a brother and sister cannot marry off the orphaness except after consulting her. And then this follows quite nicely from as an endorsement and continuation of the thought a bit earlier that Betuel was slain by an angel, because he wanted to stop the marriage - something Rashi indeed cites. And the interpretation of the yamim as the days of mourning for Betuel -- something Rashi does not cite.

Why the change? I looked it up in Mosad haRav Kook's Rashi al HaTorah, to see if they had anything, and they cited in a footnote a dvar Torah from the Nachlas Yaakov. Namely, that Rashi was expanding the statement on the basis of a gemara we just encounted in daf Yomi this week, on Kiddushin 41a. That gemara, cited lehalacha by the Rif, reads:

And thus it is not just the mother and brother marrying her off, but even the father. Even in that case, they must consult her for her consent.האיש מקדש את בתו כשהיא נערה:"A man may marry off his daughter when she is a naarah":

נערה אין קטנה לא

מסייע ליה לרב דאמר רב יהודה א"ר אסור לאדם שיקדש את בתו כשהיא קטנה עד שתגדיל ותאמר בפלוני אני רוצה:

{The implication is:} A naarah, yes, but a minor, no. This supports Rav. For Rav Yehuda cited Rav: It is forbidden for a man to marry off his daughter when she is a minor, until she grows and says "I want to be with Ploni."

I have strong doubts as to this interpretation of Rashi's modification of the wording, for a few reasons. Among them is that in context, the עד שתגדיל means when she becomes a naarah, but as a ketana it is forbidden. And that is why the Mishna chose specifically naarah, which supports that statement of Rav. The implication is not a mature ketana, but specifically a naarah. And so how could Rashi be endorsing this as a perush in this story when the characters in the story are violating it? (I suppose one could say he is selectively borrowing ideas from masechet Kiddushin, but I am not enthusiastic about this reading.) That is not to say that Rashi paskens against this gemara, but I am addressing the application of this gemara to the narrative, within Rashi's commentary.

Furthermore, Rashi copies over the wording mikan. Do they really derive the halacha in the gemara from this story? Besides the difficulty in doing so because of the mismatch, there is nothing to hint at the idea that this narrative forms the basis of Rav's prohibition.

I would rather say that Rashi had a different girsa in midrash rabba, or else was not so careful in his quotation of it, because the word yetoma was not so important for his purposes. Or maybe he removed it with purpose. This might actually help us in understanding Rashi.

Let us now turn to the question of what is motivating (rather than bothering) Rashi. There are oh so many midrashim, yet Rashi selected the midrashim he did in order to express some view of the Biblical narrative. Why is Rashi selecting this particular midrash of מכאן שאין משיאין את האשה אלא מדעתה? What does this add for him? I don't believe he was trying to teach us this halacha, and that was the sole reason for citing it. It must add something, perhaps thematically.

I see a few possibilities.

1) As mentioned earlier, Rashi channels the midrash rabba in the same section to explain the sudden disappearance of Betuel from the scene. By citing this when the mother and brother ask her, he is bolstering this idea of Betuel's death and the rise of the mother and brother, by demonstrating that they were following the appropriate guidelines for a mother and brother marrying off an orphaness.

Of course, by removing the word yetoma, if it was deliberate change, Rashi demonstrates that this is not his focus in citing this midrash. And even if it was a careless mis-citation, he demonstrates that this was not an important aspect to pay heed to, such that isha is a perfectly acceptable switch for yetoma.

2) He indeed is trying to teach people in general that they should not marry off their minor daughters without consent. We see from Tosafot on the daf that this was actually medieval practice, so maybe he was giving mussar as best he could, in context. Thus, say Nachlas Yaakov was right. I still have difficulties for the previously listed reasons.

2) He indeed is trying to teach people in general that they should not marry off their minor daughters without consent. We see from Tosafot on the daf that this was actually medieval practice, so maybe he was giving mussar as best he could, in context. Thus, say Nachlas Yaakov was right. I still have difficulties for the previously listed reasons.Or we could say that he wouldn't be condemning it, because it was after all a common and accepted Jewish practice, and we see Tosafot defending it. Assuming that Tosafot's description is applicable to Rashi's time and place as well.

3) I would assume more along the lines of the following option: Rashi is not interesting in discussing her yetoma status, and perhaps that is why he leaves it out of his citation. Rather, his interest is in how Midrash Rabba is casting what they are asking Rivkah. One would think they are just asking her if she wants to leave right away, but according to this, they are asking her the primary question of whether she wants to get married or not.

We indeed know that this is a question which concerns the pashtanim, as we see that Rashbam and Shadal argue with Rashi on this count. As Shadal writes:

התלכי עם האיש הזה : לא ייתכן שישאלו אותה, אם רצונה להינשא ליצחק, אחר שכבר אמרו : מה' יצא הדבר ; גם נראה שלא היה מנהג הקדמונים לשאול את פי בניהם ובנותיהם בענין זה, אלא האבות היו משיאין את זרעם מדעת עצמם, וכמו שאנו רואים ביצחק שלקח לו עבדו אשה שלא מדעתו ; אלא הטעם (כדברי רשב"ם ) התלכי עתה מיד עם האיש הזה או תחפצי להתעכב וללכת אחר זמן עם אחרים.

dismissing the possibility that they asked her about agreeing to the marriage, for several reasons he gives above. Rather, he is simply asking when she wants to leave.

This, then, I am fairly confident, was Rashi's motivation in citing this particular midrash, as well as why he might have chosen to emend out the word yetoma.

This, then, I am fairly confident, was Rashi's motivation in citing this particular midrash, as well as why he might have chosen to emend out the word yetoma.

No comments:

Post a Comment