In parashat Ki Teitzei, we read that after an Israelite man takes a beautiful captive woman as a wife, he must treat her as a full wife. That means that if he no longer desires her, she is not a sexual slave to be passed on to the next man who will purchase her. Rather, there is a regular divorce and she goes free as a full Israelite woman.

14 And it will be, if you do not desire her, then you shall send her away wherever she wishes, but you shall not sell her for money. You shall not keep her as a servant, because you have afflicted her.

|

|

יד וְהָיָה אִם לֹא חָפַצְתָּ בָּהּ וְשִׁלַּחְתָּהּ לְנַפְשָׁהּ וּמָכֹר לֹא תִמְכְּרֶנָּה בַּכָּסֶף לֹא תִתְעַמֵּר בָּהּ תַּחַת אֲשֶׁר עִנִּיתָהּ:

|

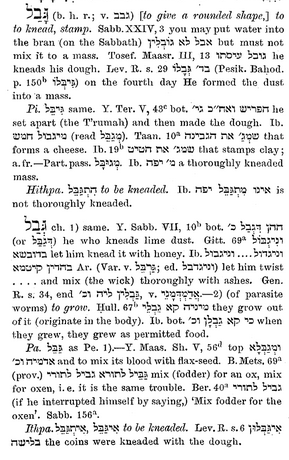

In Taama Dekra, Rav Chaim Kanievsky analyzes a midrash about this pasuk:

“וְהָיָה אִם לֹא חָפַצְתָּ בָּהּ -- Rashi explains: The Scripture is informing / predicting that you will eventually come to despise her.

And so it is in the Sifrei. And the Re’em [Rabbi Eliyahu Mizrachi] wrote: ‘I do not know from where they darshen this, for behold it [the words in the pasuk] are required for it [the law] itself.

And in my humble opinion, one can explain this based on the Midrash (in parashat Lecha Lecha), that every place where it states ויהי it is a language of pain and every place where it states והיה it is a language of joy. And so, it was difficult to Chazal why it states by divorce [as is the case in this pasuk] a language of joy [והיה]. Therefore, they darshened that the Scripture is informing you [מבשרך], and it is a besora [בשורה] tova, good news, that you will divorce her and she will not give birth for him a ben sorer umoreh. And so too in the second pasuk [Devarim 21:15] וְהָיָה הַבֵּן הַבְּכֹר לַשְּׂנִיאָה, they said in the Sifrei, ‘the pasuk is informing [מבשרך] that the firstborn son will be to the hated one, and this as well is darshened from the language of וְהָיָה, that they are mevasrim [informing of good news] to the hated wife that she will have the firstborn.”

While Rav Kanievsky does not make this absolutely explicit, he is certainly working with yet another midrash, as cited by Rashi on pasuk 11:

11 and you see among the captives a beautiful woman and you desire her, you may take [her] for yourself as a wife.

|

|

יא וְרָאִיתָ בַּשִּׁבְיָה אֵשֶׁת יְפַת תֹּאַר וְחָשַׁקְתָּ בָהּ וְלָקַחְתָּ לְךָ לְאִשָּׁה:

|

[and you desire her,] you may take [her] for yourself as a wife: [Not that you are commanded to take this woman as a wife,] but Scripture [in permitting this marriage] is speaking only against the evil inclination [, which drives him to desire her]. For if the Holy One, blessed is He, would not permit her to him, he would take her illicitly. [The Torah teaches us, however, that] if he marries her, he will ultimately come to despise her, as it says after this, “If a man has [two wives-one beloved and the other despised]” (verse 15); [moreover] he will ultimately father through her a wayward and rebellious son (see verse 18). For this reason, these passages are juxtaposed. — [Tanchuma 1]

|

|

ולקחת לך לאשה: לא דברה תורה אלא כנגד יצר הרע. שאם אין הקב"ה מתירה ישאנה באיסור. אבל אם נשאה, סופו להיות שונאה, שנאמר אחריו (פסוק טו) כי תהיין לאיש וגו' וסופו להוליד ממנה בן סורר ומורה, לכך נסמכו פרשיות הלל

|

Rashi is based on a Midrash Tanchuma Aleph[1] on parashat Ki Teitzei, which couples Rabbinic disapproval for Ben Sorer Umoreh with the general midrashic approach of darshening semuchim (juxtaposed sections), particularly in sefer Devarim.

Thus, Rav Kanievsky knows that Rashi is saying, based on a midrash, that the inevitable sad conclusion of marrying and staying married to a Yefat Toar is a Ben Sorer Umoreh. Therefore, the divorce which prevents this conclusion, constitutes good tidings, besorot tovot. And thus the midrash is based on Chazal’s derasha on the otherwise incongruous vehaya in the context of divorce.

This is a marvelous construction which creates a harmonious whole out of several different midrashim and midrashic derivations.

However, as a matter of peshat -- by which I mean the authorial intent -- of the midrash, I don’t think Rav Kanievsky is correct. Methodologically, I have the following objections:

We need not worry about ma kasheh leRashi, what is “bothering” Rashi, or indeed, what is “bothering” Chazal. This construction appears concerned with this, insofar as the answer points out an incongruity -- the happiness implied by vehaya -- that sparked the midrash. Rather, I would look towards opinion plus opportunity, such as a displeasure towards the institution of yefat toar (certainly supportable in my opinion by various portions of the pesukim on a peshat level) together with the opportunity afforded by an ambiguous Biblical text to assert a predicted unhappy conclusion.

Saying that the hatred of the married yefat toar, together with the divorce, is a happy occurrence is certainly extremely creative, but goes against the tone set by other midrashim (and as cited by Rashi in pasuk 11, that there are unhappy conclusions to his decision to wed the yefat toar.

To find peshat in any one midrash, I believe it worthwhile to consider that midrash in isolation. Creating a hodgepodge of midrashim and midrashic methods takes one away from peshat in the midrash. Here we have brought in, from left field, the midrashic method of vayhi vs. vehaya, with happiness as a message. Sure, that is possibly supported by the language of besorah, but that feels like very tenuous support. We ignore the darshening of semuchin from Tanchuma and Rashi, but it is there at the least if we are going to be considering Rashi. Though perhaps, when focusing just on Sifrei, we should indeed ignore the darshening of semuchin.

Meanwhile I feel that there is a more obvious and simple derivation for the Sifrei, also centered on vehaya.

If we just focus on the two midrashim in the Sifrei, I would posit the following derivation. All examples pulled from Devarim perek 21 and perek 22. The Torah employs specific words to connote a condition. For instance, כִּי תִהְיֶיןָ לְאִישׁ שְׁתֵּי נָשִׁים, if a man has to wives. Of כִּי יִהְיֶה לְאִישׁ בֵּן סוֹרֵר וּמוֹרֶה, if a man has a rebellious son. The word ki introduces something which might happen, and explains what regulations cover that situation. Alternatively, the Torah might employ im to denote if. וְאִם לֹא קָרוֹב אָחִיךָ אֵלֶיךָ, and if your brother [who lost the ox] is not in close proximity to you.

Meanwhile, the word והיה is regularly employed not to indicate a conditional but the next logical event in a progression. For example, וְהָיָה בְּיוֹם הַנְחִילוֹ אֶת בָּנָיו, and it will be on the day he bequeaths property to his sons. וְהָיָה הָעִיר הַקְּרֹבָה אֶל הֶחָלָל, and it will be that the city closest to the corpse will have its elders perform the ritual of egla arufa. וְהָיָה עִמְּךָ עַד דְּרשׁ אָחִיךָ אֹתוֹ וַהֲשֵׁבֹתוֹ לו, by keeping the lost ox in your possession, it will be with you when your non-proximate neighbor seeks it out.

That does not mean that וְהָיָה cannot connote a conditional; just that it is regularly employed to connote a definite.

Suddenly, in pasuk 14, we have וְהָיָה coupled with אִם.

14 And it will be, if you do not desire her, then you shall send her away wherever she wishes, but you shall not sell her for money. You shall not keep her as a servant, because you have afflicted her.

|

|

יד וְהָיָה אִם לֹא חָפַצְתָּ בָּהּ וְשִׁלַּחְתָּהּ לְנַפְשָׁהּ וּמָכֹר לֹא תִמְכְּרֶנָּה בַּכָּסֶף לֹא תִתְעַמֵּר בָּהּ תַּחַת אֲשֶׁר עִנִּיתָהּ:

|

Is it “if” or is it “it will be”. The answer, according to the Sifrei, is that while this is given as a conditional law, since it describes what is to happen if he doesn’t like her, in fact, it is a certainty or near-certainty that this conditional will come to happen. Thus, it is both וְהָיָה and with אִם. And if you need a midrashic hook, you can say it is the incongruity of the וְהָיָה coupled with the אִם which sparks the midrash.

There is also the Rabbinic displeasure with the yefat toar (that it is a Biblical compromise) impelling this interpretation. The same motivation which impels the Midrash Tanchuma to darshen semuchin to assert this unhappy result was the inevitable conclusion impels the Sifrei to darshen the וְהָיָה coupled with the אִם

So much for the first Sifrei. As for the second Sifrei, it is on pasuk 15:

15 If a man has two wives-one beloved and the other despised-and they bear him sons, the beloved one and the despised one, and the firstborn son is from the despised one.

|

|

טו כִּי תִהְיֶיןָ לְאִישׁ שְׁתֵּי נָשִׁים הָאַחַת אֲהוּבָה וְהָאַחַת שְׂנוּאָה וְיָלְדוּ לוֹ בָנִים הָאֲהוּבָה וְהַשְּׂנוּאָה וְהָיָה הַבֵּן הַבְּכֹר לַשְּׂנִיאָה:

|

On a peshat level, the word וְהָיָה is just continuing to describe an element of the conditional started by כִּי תִהְיֶיןָ. That is, this pasuk sets up the situation, and so וְהָיָה is warranted as a simple continuation of the situation. One need not repeat ki or vechi. And the conclusion of what regulations control the situation begins the next pasuk.

However, on a midrashic level, especially after the previous similar derasha on the immediately preceding pasuk, we are primed to read this וְהָיָה as another inevitable conclusion. This is not peshat, but it is midrash, taking advantage of the ambiguity of language to read the pasuk in an unexpected and totally novel manner. And so, it is the hatred of the wife that will almost guarantee that the bechor will be granted to the disfavored wife.

Why should this be so? Hashem favors the underdog. We need look no further than the canonical hated and beloved wives to see this. In parashat Vayeitzei, Bereishit 29, with the birth of Reuven the bechor to Leah, when Rachel was barren:

And the Lord saw that Leah was hated, so He opened her womb; but Rachel was barren.

|

|

לא וַיַּרְא ה כִּי שְׂנוּאָה לֵאָה וַיִּפְתַּח אֶת רַחְמָהּ וְרָחֵל עֲקָרָה:

|

As such, we have no need to travel far away to bring in a completely separate derasha, about vehaya generally meaning happiness, which doesn’t seem to fit the context and thus sparks the midrash. This simply isn’t what Chazal mean. And so, I would deem the innovative interpretation of the midrash to be a brand new, neo-midrash, from a Gadol baTorah, but still not at all the intent of the midrashic author of the Sifrei.

Since we are discussing Rav Chaim Kanievsky and how vehaya can be midrashically reinterpreted from a possibility to mean a definite and a prediction, it seems proper to discuss Rav Chaim Kanievsky and how his words were reinterpreted from a hopeful possibility to mean a definite and / or a prediction. As we’ve seen many times in the past, some of the people surrounding Rav Kanievsky are idiots, who regularly misinterpret his words to be messianic predictions. In response to such reports that he has issued a messianic prediction, Rav Kanievsky is on record as saying that this is “shtuyot”, nonsense, but this doesn’t prevent the idiots from continuing to turn his words into a choyzek.

The latest such attempt was reported at Yeranen Yaakov:

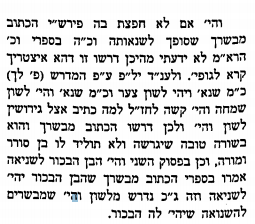

As with every statement attributed to Rav Chaim Kanievsky, this statement must be triple-checked and verified before believed.

Emotional moments in the home of the Prince of Torah Haga'on Rav Chaim Kanievsky Shlit"a who hosted in his home the chairman of Yad Sarah - Rav Moshe Cohen - and the director of the emergency switchboard and home hospitalization program - Rav Nachum Gitman - who accepted his blessing.

At the focus of the visit stood the initiative to install an emergency button in synagogues and Mikva'ot. They were discussing a new initiative from Yad Sarah that was born against the backdrop of a deteriorating security situation.

During the visit, the button and the mode of operation of the emergency switchboard of Yad Sarah were presented to the Ga'on Rav Chaim Kanievsky Shlit"a. The Ga'on Rav Chaim Kanievsky's response was "Mashiah will come before the holidays and you won't need to install any more emergency buttons." Additionally, the rav blessed the switchboard operators with blessings of success.

...

To give some background not in the translation, Rav Elyashiv zatza”l had approved certain mechanism by which emergency buttons, installed in shuls, could be used with zero or minimal halachic problems on Yom Tov. On a weekday, in case of emergency, one can use a cell phone to call for help. But an emergency button is faster, and on Yom Tov people won’t be carrying phones. And, as someone in the article notes, on Yom Tov, there are more people in shul. They brought these emergency buttons to Rav Chaim Kanievsky, who is Rav Elyashiv’s son-in-law and a living Gadol, to examine, and presumably as a photo-op / promotion. He gave a blessing:

עד החגים יבוא משיח ולא תצטרכו להתקין יותר לחצני מצוקה

“Before Yom Tov arrives, [may it be] that Mashiach will arrive, such that we will not need any emergency buttons.”

As the first commenter at Kooker says:

בטוח אמר זאת מתוך אמונה ותפילה, וכמשאלה הרי אנחנו מחויבים להאמין ולחכות לו בכל יום שיבא, ולא כנבואה.

I would say that this is the jussive. Hebrew can be ambiguous, and the jussive or subjunctive (“let there be light”, “may there be light”) can sometimes be expressed in the same way as the perfect (“there will be light”). Rav Kanievsky was expressing a hope and a blessing, but overeager people took his words and corrupted them to mean a prediction.

There was a story that happened last week that caused all the ruckus. A young girl who had recently died reportedly came to her father in a dream saying that on Thursday, the day after a solar eclipse, Mashiach would come. The father went to Rav Kanievsky to relate the story and Rav Kanievsky supposedly told his family (after) to purchase a new suit for Thursday (presumably with which to greet Mashiach). This created the ruckus.

The story was later denied by the family of Rav Kanievsky and explained as a misunderstanding. Rav Kanievsky was asked by an avreich about purchasing a new suit for a wedding, and he answered with a smile and a joke that maybe Mashiach will come and he will also be able to use the suit for that. That is the source for the balagan, as reported by Mishpacha magazine (Hebrew edition).

----------------------

Footnotes:

[1]

http://hebrewbooks.org/pdfpager.aspx?req=20318&st=&pgnum=131

[2]

http://hebrewbooks.org/pdfpager.aspx?req=20318&st=&pgnum=133

[3] The Midrash Tanchuma as we have it seems like it might be a little different in message:

כי תצא למלחמה

שנו רבותינו:

מצוה גוררת מצוה, ועבירה גוררת עבירה.

וראית בשביה וגו', וגלחה את ראשה ועשתה את צפרניה

כדי שלא תמצא חן בעיניך.

מה כתיב בתריה?

כי תהיין לאיש שתי נשים וגו'. שתים בבית, מריבה בבית.

ולא עוד, אחת אהובה ואחת שנואה, או שתיהן שנואות.

מה כתיב אחריו?

כי יהיה לאיש בן סורר ומורה.

כל מאן דנסיב יפת תאר, נפיק מנייהו בן סורר ומורה.

That is, one mitzva leads to another mitzvah and one aveira leads to another aveira. The purpose of the growing of her nails and shaving of her head is to make her unattractive, so that you don’t marry her. Written immediately afterwards is the case of a man with two wives. Two wives in the house, discord is in the house, and not only that, one if loved and the other is hated, or both are hated. Written immediately afterwards is the Ben Sorer Umoreh. Whoever marries a beautiful captive woman, from her will emerge a Ben Sorer Umoreh.

This midrash Tacnhuma looks at both Yefas Toar and polygamy as much less than the ideal. This Rabbinic disapproval couples with the general midrashic approach of interpreting juxtaposed sections (darshening semuchos), especially in sefer Devarim, to say that one juxtaposed bad result is the inevitable conclusion of the earlier bad action.

Rashi clearly understands Midrash Tanchuma as saying both the hatred and rebellious son stem from marrying the beautiful captive. This might well be what our Midrash Tanchuma is saying, but besides this, Rashi works off Midrash Tanchuma Aleph, which often differs in details from our Midrash Tanchuma.