Post: People are medakdek in the slightest thing in Rashi, and often they are wrong to do so. Here is a Rashi towards the beginning of parashat Metzora:

| 4. Then the kohen shall order, and the person to be cleansed shall take two live, clean birds, a cedar stick, a strip of crimson [wool], and hyssop. | ד. וְצִוָּה הַכֹּהֵן וְלָקַח לַמִּטַּהֵר שְׁתֵּי צִפֳּרִים חַיּוֹת טְהֹרוֹת וְעֵץ אֶרֶז וּשְׁנִי תוֹלַעַת וְאֵזֹב: | |

| חיות: פרט לטרפות: | ||

| טהרות: פרט לעוף טמא. לפי שהנגעים באין על לשון הרע, שהוא מעשה פטפוטי דברים, לפיכך הוזקקו לטהרתו צפרים, שמפטפטין תמיד בצפצוף קול: |

Thus chayos means that they are still alive, and perhaps even not alive yet soon to die, having been torn. Tehoros means that they are of a kosher species.

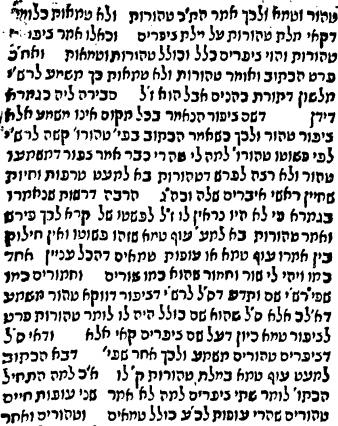

Mekorei Rashi points us to the Sifra and to Chullin daf 140a (Aramaic and English summary). To just quickly look to the Sifra:

And see the gemara as well inside. Tehoros is indeed ambiguous. Does this mean ritually impure? Tamei because of being a neveilah? Or does it mean a non-kosher species. Looking at various sources, including the gemara, it is clear that it means non-kosher species. Yet, there is this ambiguity. And this ambiguity is present in the gemara, as well, when it says things like:

ת"ש מסיפא טהורות מכלל דאיכא טמאות לא מכלל דאיכא טרפותRashi makes this much clearer, by reiterating the word of and putting tamei in the singular. Once again:

טהרות: פרט לעוף טמא.This is a divergence from the language of the gemara and the Sifra. But it makes things exceptionally clear. Why? Because "of tamei" and "of tahor" are established as collocations, words which go together more often than random chance. Why? Because they are an established name for "non-kosher species of bird" and "kosher species of bird". In contrast, just the word טמאות appears as an adjective in multiple contexts. And since we are referring to this known entity, it makes sense to call it of tamei in the singular, which is how we most often encounter it. Thus, if we do a search at Snunit for עוף טמא, we find 48 matches, indeed some on the same daf in Chullin. If we do a search for עופות טמאות, we find 0 matches. I know that if I heard the term in plural, I would not immediately leap to the interpretation of "non-kosher birds", but when I read it is Rashi in the singular, I indeed made that correct association. So shkoyach, Rashi, for writing a clear peirush.

But apparently some meforshei Rashi took this as a cue to wrongly make diyukim, and attribute to Rashi things he never intended. (See this parshablog post about this problem in general).

Gur Aryeh, that is, the Maharal, debunks this for us:

"to exclude oph tamei -- There are those who are medakdek into the words of Rashi, that at first he wrote 'chayos to the exclusion of treifos' {in plural, without modification of oph or ophos} and afterwards he wrote 'tehoros, to the exclusion of oph tamei', and he did not say 'to the exclusion of temeios'.

And this is no dikduk, for had I said 'and not temeios', this would have been that it was not rendered ritually impure from tum'ah. Therefore he said 'to the exclusion of oph tamei', whose explanation is that it is impure in its species {=a non-kosher species}. And he did not say 'to ophos temeios' {which would include the word ophos, implying the species}, for I would have already said that it means to birds which had become ritually impure, but in the phrase oph tamei, there is no room to err, for its meaning is certainly a species of non-kosher bird, for about the species one speaks in the singular. Therefore he said it in the singular, 'to the exclusion of oph tamei'. And this is obvious."

I agree in general with his conclusions and arguments, though not necessarily in all the particulars. And what I wrote above bolsters and works in parallel to his arguments. One point he missed was that this is a divergence from the Sifra.

Who, precisely, is he arguing against? Note footnote 32 in Gur Aryeh, which states that he could not find his source; but that the Divrei David {=the Taz} asks the same, so you can check that out. I can point to someone subsequently argues on Gur Aryeh, and bolsters the dikduk into Rashi's language: the Levush HaOrah, Rabbi Mordechai Yoffe, who is Gur Aryeh's contemporary, born in Prague, and a descendant of Rashi. I present here the Levush:

First he quotes the Rashi and the Maharal which we saw above. Then, he writes:

"And I am astonished at this Rav {=Gur Aryeh} about that which he says. Who was the prophet who informed him that on the language of ophot temeiot there is room for error and to say that it is speaking about birds which had become ritually impure, while on the language of oph tamei one cannot err to say this?! I don't know upon what he relies to say so, for what is the greater strength of this than that? This is only words of prophecy! For certainly, there is in this {singular} language the connotation of the species of non-kosher bird, just as in {Bereishit 32:6, in Vayishlach} וַיְהִי-לִי שׁוֹר וַחֲמוֹר, etc., where its explanation is the species of bovine. But it can support as well the explanation of a bird which had become ritually impure {and is thus equally ambiguous}, so why should someone not make an error?

And furthermore, more than this, I say that he was dozing and sleeping when he said

this matter, and did not know what he was saying. For where in the world do we find living creatures becoming ritually impure in their lifetimes, except for the species of mankind; delve into all the halachot of the laws of ritual impurity and find it such. For there is not a single living creature which is subject to ritual impurity in its lifetime, except for man. And even within mankind, as well, it is specifically Israelites and not gentiles, Biblically speaking. And if so, the question returns to its place.

And furthermore, there are those who are medakdek into the language of Rashi, that he said 'to the exclusion of oph tamei' and he juxtaposed immediately after it to say 'because skin afflictions come because of lashon hara, etc.' they ask what the connection is of this to that? How does he connect the reason of 'because afflictions come...' with 'to the exclusion of oph tamei?

They further ask upon Rashi, za"l, from the fact that he excluded oph tamei from the word in the pasuk טְהֹרוֹת, and did not exclude it from the word צִפֳּרִים, which implies that according to Rashi, the term צִפֳּרִים includes both non-kosher birds and kosher birds, and therefore the Scripture was required to write טְהֹרוֹת, to exclude non-kosher ones. Meanwhile, we explicitly say in the gemara, in perek Shiluach haken that in all places it states tzipor, it implies a kosher bird. {Josh: This is that same gemara in Chullin we referenced above.}

And I say that all of these men {who made this diyuk} are complete with us, but they did not plumb the full depths of Rashi, zal. And just the opposite! That which Rashi was careful in his language to say upon the word טְהֹרוֹת that it is to the exclusion of oph tamei and changed from the language which is taught in Toras Kohanim {=the Sifra we saw above}, טְהֹרוֹת and not טמאות, he is displaying to us his great wisdom, comprehensive expertise and the depth of his investigations. For he certainly maintains that Toras Kohanim argues on our gemara, and holds that the term tzipor includes and teaches regarding both a kosher bird

and a non-kosher bird. And therefore Toras Kohanim said טְהֹרוֹת and not טמאות, that is to say that the word טְהֹרוֹת is modifying צִפֳּרִים. And so it is as if it stated tziporim tehorot, and so the 'birds' are a klal, general statement, and includes both kosher and non-kosher, and afterwards the Scriptures specifies and says tehorot and not non-kosher. So was implied to Rashi from the language of the Sifra.

However, he {=Rashi}, zal, maintains like our gemara, that the term tzipor which is stated in every place only connotes a kosher bird, and therefore, then the Scripture states explicitly tehorot, it is difficult to Rashi, since the peshat-level of tehorot, what is it for? For behold it was already stated tzipor, which connotes tahor {=kosher species}; and he did not wish to explain that tehorot comes to exclude treifos and chayos that their limbs are living {=complete}, and the like, many derashot which are stated in the gemara {in Chullin}, because they did not seem compelling to him, za'l, according to the peshat of the Scriptures. Therefore he explained and said tehoros comes to exclude oph tamei, which is the simple {peshat} explanation, and there is no difference between saying oph tamei and ophot temei'im, for all are one matter, just like וַיְהִי-לִי שׁוֹר וַחֲמוֹר, which is like shorim and chamorim, just as Rashi explains there.

And know that Rashi maintains that tzipor specifically implies kosher {tahor}; for if not so, but rather he held that it is a term which encompasses, he should have said 'tehorot to the exclusion of tzipor tamei, since it was modifying the word צִפֳּרִים. Rather, he certainly maintains the צִפֳּרִים implies kosher ones. And therefore, after he explains that the Scriptures come to exclude an oph tamei with the word טְהֹרוֹת, it is difficult for him, if so, why the verse began by stating שְׁתֵּי צִפֳּרִים. Why did it not say {the more generic} shtei ophot chayim tehorim, for ophot, according to everyone, encompasses non-kosher and kosher,

and afterwards say the exclusion of טְהֹרוֹת, for such is the measure throughout the Torah, to write first the klal {general}and afterwards the prat {particular}? Upon this he continues to explain, and says that since these afflictions come because of lashon hara, etc., therefore it was required to purify him with tziporim, which chirp, etc. That is to say, for this reason it was written first tziporim, for it {the word tziporim} was not coming to exclude non-kosher birds, but rather to darshen from it and to say that we requiring a constantly chirping and tweeting bird, which does so each morning, for this is the connotation of the term tzipor, as the Ramban zal wrote, that the name tzippor encompasses small birds which rise early in the morning to chirp and to sing, from the Aramaic term tzafra. End quote of the Ramban. And it appears to me {=the Levush HaOrah} that so, too, is the position of Rashi, zal, in what he juxtaposed 'because skin afflictions' immediately following 'to the exclusion of oph tahor'. And this appears to me clear and obvious, within the position of Rashi, za'l. And the law of the purification of the leper, according to the position of Rashi, is specifically {?} with a kosher bird which is small, which has the behavior of chirping and singing every morning. Alternatively, all chirpers are called tzippor based on {the Aramaic word for boker,} tzafra, even if they are not small, it seems to me."

So ends the Levush HaOrah. If you asked me who won this dispute, I would say that Gur Aryeh is certainly the winner here. The only point I would possibly grant him is that perhaps there is no distinction which should be made between the plural and singular of oph tamei, and that one should not make anything of it. I think he is incorrect on every other point, and is reading intentions into Rashi which Rashi never dreamed of. I will answer each of Levush HaOrah's objections and suggestions, on behalf of Gur Aryeh.

1) Levush HaOrah wrote:

Who was the prophet who informed him that on the language of ophot temeiot there is room for error and to say that it is speaking about birds which had become ritually impure, while on the language of oph tamei one cannot err to say this?!I already explained above, based on searches through Rabbinic literature, that one is a common phrase while the other is not. And I would add Gur Aryeh's point that an irregular singular is more clearly a reference to the species, while the plural, [Josh: at least in this instance where we are dealing with two birds], could be taken to be the two actual physical birds. This is not a matter of prophecy. It is a matter of literary sense. It is libi omer li. Eventually, with proper training and a lot of experience reading texts, one develops this sense. But it is not necessarily something that one can put a finger on, and define in overly precise terms. Gur Aryeh is right in evaluating what is more ambiguous and less ambiguous to the casual learned reader.

2) Levush HaOrah wrote:

And furthermore, more than this, I say that he was dozing and sleeping when he said this matter, and did not know what he was saying. For where in the world do we find living creatures becoming ritually impure in their lifetimes, except for the species of mankind; delve into all the halachot of the laws of ritual impurity and find it such. For there is not a single living creature which is subject to ritual impurity in its lifetime, except for man. And even within mankind, as well, it is specifically Israelites and not gentiles, Biblically speaking. And if so, the question returns to its place.He is right, he is right, he is right, until finally, he is wrong. Gur Aryeh was certainly not dozing or slumbering when he wrote this. Gur Aryeh was not proposing that this was a valid derasha for someone to make. Indeed, if it were, why not make such a drasha in the pasuk? And you might need to demonstrate that that was not what the Sifra meant. But it is not really a possible derasha. Instead, it is an ambiguity that the casual or non-casual reader might make.

Let me choose an ambiguous English sentence, to demonstrate. I will use a garden-path sentence:

The horse raced past the barn fell.Now, you may ask, what in the world is this thing called a 'barn fell'? I don't know much about farming, so I've never heard of such a barn fell. There is, in fact, no such thing. But we travel down one garden path of interpretation, and when we encounter the word 'fell', we don't know what to do.

The ambiguity which confused us was that 'raced' is both an active verb and a passive verb. As an active verb, it means that the horse ran swiftly. As a passive verb, it means that others made it run quickly. We are using it in its passive sense.

They raced a black horse past the house. They raced a brown horse past the barn. The horse raced past the barn fell.That is,

The horse, which was raced past the barn, fell.The word 'fell', then, is a verb. This makes for a perfectly grammatical sentence which, in certain contexts, is still enormously confusing. One person might think there is something actually called a 'barn fell'. Someone else might think the author made a typographical error somewhere. Someone else might puzzle it out for a minute, or might finally be informed by someone else of the true parsing of the sentence.

The Levush HaOrah would insist that this garden path sentence, 'The horse raced past the barn fell', is entirely unambiguous. After all, there is no such thing as a 'barn fell'! Therefore, it must mean what I explained it to mean, above. And, if some author took pains to write 'The horse, which was raced past the barn, fell', it is entirely unwarranted, and that author is trying to teach us something extra. Anyone who suggests that the author was just striving for clarity must be dozing or sleeping!

In the previous paragraph, I was making a rhetorical point. The Levush HaOrah would not say that. But the case with his analysis of Gur Aryeh's point. Gur Aryeh was not trying to argue that a 'barn fell' was a real thing, or that living animals are actually susceptible to ritual impurity. But the casual reader might not remember this, or might see the unadorned word tehorot and think that it refers to such a thing. And the scholarly reader might need to take a minute to work out that it should not mean this, or might even think that here is a source which makes the opposite assumption. Perhaps it is a daas yachid. Eventually, hopefully, we come to the correct conclusion, but this confusion and ambiguity would be the fault of the author. Gur Aryeh is saying that Rashi is a skilled writer, who took steps to avoid this confusion, and so made the more explicit oph tamei instead of the more ambiguous temeiot, which does refer to ritual impurity in other contexts.

If so, there is no question to be resolved, and all the other kvetches are unwarranted.

3) Levush HaOrah further writes, approvingly,

And furthermore, there are those who are medakdek into the language of Rashi, that he said 'to the exclusion of oph tamei' and he juxtaposed immediately after it to say 'because skin afflictions come because of lashon hara, etc.' they ask what the connection is of this to that? How does he connect the reason of 'because afflictions come...' with 'to the exclusion of oph tamei?Sometimes semichut, juxtaposition, should be interpreted. But sometimes, it should not be. I will account for this juxtaposition, in what I consider to be a straightforward manner. (And which I've suggested for other Rashis in the past -- for the most recent example, see here.) Rashi pulls his commentary from different sources. We saw, earlier, in Mekorei Rashi, that Rashi draws the first two comments the Sifra, which is Midrash Halacha. If we look at Mekorei Rashi as to the source of the next three Rashis, we find that it is from Midrash Tanchuma and from masechet Arachin, 16b. Thus, Tanchuma, Vayikra 14, siman 3:

ביום טהרתו כמה?This is from Midrash Aggadah. After the three selections of Midrash Aggadah, Rashi returns to selectively cite midrash halacha, from the Sifra. Thus, see these Rashis. I highlight the midrash halacha in red and the midrash aggadah in blue:

שתי צפרים חיות טהורות.

מה נשתנה קרבנו משאר קורבנות?

על שספר לשון הרע.

לפיכך אמר הכתוב: יהא קרבנו שתי צפרים, שקולן מוליכות.

| 4. Then the kohen shall order, and the person to be cleansed shall take two live, clean birds, a cedar stick, a strip of crimson [wool], and hyssop. | ד. וְצִוָּה הַכֹּהֵן וְלָקַח לַמִּטַּהֵר שְׁתֵּי צִפֳּרִים חַיּוֹת טְהֹרוֹת וְעֵץ אֶרֶז וּשְׁנִי תוֹלַעַת וְאֵזֹב: | |

| חיות: פרט לטרפות: | ||

| טהרות: פרט לעוף טמא. לפי שהנגעים באין על לשון הרע, שהוא מעשה פטפוטי דברים, לפיכך הוזקקו לטהרתו צפרים, שמפטפטין תמיד בצפצוף קול: | ||

| ועץ ארז: לפי שהנגעים באין על גסות הרוח: | ||

| ושני תולעת ואזב: מה תקנתו ויתרפא, ישפיל עצמו מגאותו, כתולעת וכאזוב: | ||

| עץ ארז: מקל של ארז: | ||

| ושני תולעת: לשון של צמר צבוע זהורית: |

The purpose of citing these midreshei aggadah is to deal with the why. What is the symbolism of the birds, the ceder wood, the tongue of red {=worm} wool, and the hyssop? This is important to understand, on the peshat level.

Would it have been appropriate to put לפי שהנגעים באין על לשון הרע, technically based on the tzipporim aspect, first? Maybe that would have also worked out. But the approach Rashi seems to have chosen here is to have runs of midrash halacha and midrash aggadah. (1) He analyzes the adjectives related to tzipporim, and cites appropriate midrash halacha on it. (2) Then, he transitions to midrash aggadah and so, before moving off of the topic of tzipporim, explains the symbolism of tzipporim. (3) Then, since he is in midrash aggadah mode, he continues on to explain the symbolism of the eitz erez, shni tolaas and the eizov. This is excellent writing style, for all symbolism is placed together. (4) Finally, since he has completed his discussion of the symbolism, he returns to midrash halacha in order to explain just what this eitz erez and shni tolaas are.

This juxtaposition, then, is all fairly straightforward from a literary perspective. But it is just this sort of literary approach that Levush HaOrah ignores. Then, non-questions become questions and they become the impetus for non-questions.

4) Levush HaOrah further writes:

For he certainly maintains that Toras Kohanim argues on our gemara, and holds that the term tzipor includes and teaches regarding both a kosher bird and a non-kosher bird. And therefore Toras Kohanim said טְהֹרוֹת and not טמאות, that is to say that the word טְהֹרוֹת is modifying צִפֳּרִים.I think he is certainly correct up to here, that the Sifra has different assumptions, and therefore draws different conclusions, than the gemara.

5) But then,

However, he {=Rashi}, zal, maintains like our gemara, that the term tzipor which is stated in every place only connotes a kosher bird, and therefore, then the Scripture states explicitly tehorot, it is difficult to Rashi, since the peshat-level of tehorot, what is it for?

...

Therefore he explained and said tehoros comes to exclude oph tamei, which is the simple {peshat} explanation, and there is no difference between saying oph tamei and ophot temei'im, for all are one matter, just like וַיְהִי-לִי שׁוֹר וַחֲמוֹר, which is like shorim and chamorim, just as Rashi explains there.

And know that Rashi maintains that tzipor specifically implies kosher {tahor}; for if not so, but rather he held that it is a term which encompasses, he should have said 'tehorot to the exclusion of tzipor tamei, since it was modifying the word צִפֳּרִים. Rather, he certainly maintains the צִפֳּרִים implies kosher ones. And therefore, after he explains that the Scriptures come to exclude an oph tamei with the word טְהֹרוֹת, it is difficult for him, if so, why the verse began by stating שְׁתֵּי צִפֳּרִים. Why did it not say {the more generic} shtei ophot chayim tehorim, for ophot, according to everyone, encompasses non-kosher and kosher, and afterwards say the exclusion of טְהֹרוֹת, for such is the measure throughout the Torah, to write first the klal {general}and afterwards the prat {particular}? Upon this he continues to explain, and says that since these afflictions come because of lashon hara, etc., therefore it was required to purify him with tziporim, which chirp, etc. That is to say, for this reason it was written first tziporim, for it {the word tziporim} was not coming to exclude non-kosher birds, but rather to darshen from it and to say that we requiring a constantly chirping and tweeting bird, which does so each morning, for this is the connotation of the term tzipor, as the Ramban zal wrote ...Here is where I disagree. This is not the realm of pesak. And even if in general on a peshat level he maintains that this is the meaning of tzipporim, Rashi is not going to consistently cite one source but disagree with its very premise, and so become a Tanna and start darshening the pesukim himself from scratch.

And even if you say that, after all, he is drawing this from existing derashot, those don't seem to rely on the same premises as Rashi. For example, I don't really imagine that the Midrash Tanchuma, or the brayta in Arachin, half-agree and half-disagree with the gemara in Chullin and the Sifra. And that if one would wholly accept all premises of one of them, the symbolism of the birds fails to apply.

6) Levush HaOrah continues:

as the Ramban zal wrote, that the name tzippor encompasses small birds which rise early in the morning to chirp and to sing, from the Aramaic term tzafra. End quote of the Ramban. And it appears to me {=the Levush HaOrah} that so, too, is the position of Rashi, zal, in what he juxtaposed 'because skin afflictions' immediately following 'to the exclusion of oph tahor'.I don't think that Ramban is necessarily correct. It seems like a bit of a kvetch. But this is what sometimes happens when you have limited access to all the Semitic languages; you make what pluasible connections you can make.

But I don't know that Rashi must accept this novel Ramban, if Rashi did not himself put forth this etymology explicitly. I also dislike the turning of this midrash aggadah, teaching the symbolism, into binding midrash halacha. This seems to me to be due to the same deafness of literary sense/

Regardless, at the end of the day, this is all unnecessary, for we have already accounted for both the change to oph tahor are for the juxtaposition for tzipporim. Therefore, despite Levush HaOrah's many objections and analyses, I side with Gur Aryeh here.

No comments:

Post a Comment